Some final thoughts on Hanukkah as we say farewell to this complex holiday:

I’m mindful that many of us struggle to find meaning in the historical events commemorated by Hanukkah. It’s a complicated story that I won’t recount in detail here other than to say that the “heroic” Maccabees were actually religious zealots who engaged in a civil war with the assimilated Hellenistic Jews of their day – and that when they succeeded in overthrowing the Seleucid empire, the independent Hasmonean commonwealth they established was corrupt and oppressive. This period of Jewish independence lasted a little more than 100 years before the Hasmoneans fell to the Roman empire.

The rabbis of classical Pharisaic Judaism were not, to put it mildly, fans of the militaristic, corrupt shenanigans of the Maccabees and the Hasmonean dynasty, which is why this story is nowhere to be found in rabbinic writings (and why the books of the Maccabees were not canonized as part of the Hebrew Bible). The Rabbis knew this all too well: empires, nations and states are artificially-created entities, manufactured through military might and inevitably destined to fall. It was not by coincidence that the famous line from Zechariah: Not by might and not by power but by My spirit says the Lord of Hosts was chosen to be the prophetic portion chanted on the Shabbat of Hanukkah.

Their famous Talmudic story about rededication of the Temple in Jerusalem and the cruse of oil that miraculously lasted for eight days is much more than a quaint legend. At its heart it’s a spiritual-political allegory about the limits of human military power – and the enduring resilience embodied by faith and light. Although the short-lived victory of the Maccabees is valorized by political Zionism and the state of Israel, I’d argue that the enduring aspect of this holiday is a rejection of the ephemeral, temporary nature of empire and state power – and the recognition of a Power yet greater.

This Faustian bargain with state power is also at the heart of this week’s Torah portion, Parashat Vayigash, in which Egypt becomes ravaged by famine. In response, Joseph (who is second in power only to Pharoah) offers to sell the Egyptians their own food back to them from Pharaoh’s storehouses that they had previously stocked. When they run out of money, they sell him their livestock. When they run out of livestock, he buys up their land. In the end, the only things they have left to sell are their own bodies and their labor, so they agree to become indentured servants (i.e., slaves) to Pharaoh.

This part of the Joseph story, needless to say, is not an easy read. Over the years, my shocked Torah study students have compared Joseph’s draconian policies to the mandatory collectivization of agriculture in Maoist China and the US government’s foreclosure of mortgages/repossession of Dust Bowl farms during the Great Depression. Among other things, this episode offers a stark commentary on the wages of absolute political power, and how this power is invariably built upon shaky and precarious foundations. (We will learn about this all too soon when we get to the Exodus story and meet “the Pharaoh who knew not Joseph.”)

The Jewish liberation theologian Marc Ellis, of blessed memory, wrote and spoke a great deal about the complex interface between Jews and power in the post Holocaust era, viewing Jewish state power embodied by the state of Israel as fatally “Constantinian.” At the same time, however, he had no desire to return to the days of Jewish disempowerment at the hands of Christian Europe. “Jewish empowerment,” he once said in an interview, “is important and should be affirmed…I want Jews to be empowered and act justly. Of course, minority communities around the world need empowerment, too. My ideal, which includes Palestinians, is an interdependent empowerment.”

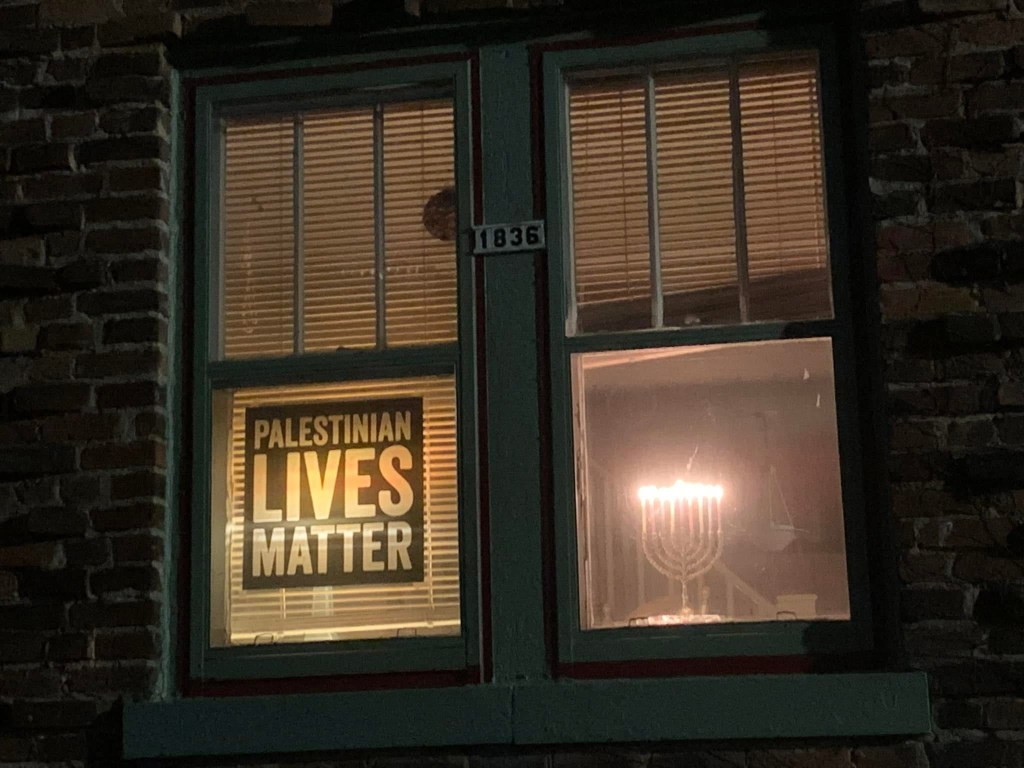

With Hanukkah now behind us, I’m more convinced than ever that this is the sacred core of that holiday: not the ignoble story of the Maccabees and the ill-fated Hasmonean Kingdom, but the light-filled spirit of interdependent empowerment. Let us hold onto this vision as Hanukkah recedes into the daunting challenges of the new year 2025. Let us put our trust in a Power yet greater than the power of the mightiest empire. Let us reject narratives that glorify nationalism and militarism – and instead embrace a vision of Judaism rooted in justice, peace, and collective liberation.