The most memorable aspect of my Pesach this year? A combination Passover – Good Friday service JRC held together with the wonderful folks at Lake Street Church of Evanston.

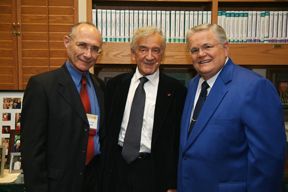

The whole thing was hatched somewhat by chance. A month or so ago I was having lunch with my good friend Reverend Bob Thompson of Lake St. Church (appropriately enough at Evanston’s Blind Faith Cafe) and our conversation turned to our respective upcoming rites of spring. Bob mentioned to my surprise that he hadn’t celebrated Good Friday at Lake St. in quite some time – mainly because he simply couldn’t abide by blood atonement theology – the notion that God would somehow require the bloodshed of one man to atone for all of the sins of the rest of the world.

For my part, I mentioned that Good Friday had not generally been so “good” to the Jews throughout history, since this was invariably the time in which the worst pogroms were perpetrated against European Jewish communities. As a result, for much of Jewish history Passover was a secret ritual: observed in fear and in private. Given our complicated mutual history, we both agreed that it would be enormously powerful to celebrate Passover and Good Friday together in a spirit of healing and hope.

So that is exactly what we did this last Friday. While Bob and I weren’t at all sure if this service would fly, it actually suceeded beyond our highest expectations. Hundreds of JRC and Lake St. members filled the sanctuary at Lake St. church. Together we celebrated with a service that mixed Hebrew and English, Jewish songs, Christian hymns and prayers for healing. We ended with a rousing “Down By The Riverside.” Afterwards, countless participants – both Jewish and Christian – told us that the service was an immensely moving and healing experience for them.

During the service, Bob and I had a conversation in which we both mused about what our respective holidays might look like if we recast them in the spirit of healing and hope. Bob began by saying the first thing Christians needed to do when celebrating Good Friday was to apologize to the Jewish community for the legacy of Christian anti-Semitism. He then went on to explore how Christians might recast the meaning of the crucifixion itself. Here’s what he had to say:

Every Good Friday well meaning folk gather to listen to priests and ministers talk about how Jesus was crucified, the “lamb of God,” to take away the sins of the world. In other words, Jesus died a sacrificial death to satisfy the God who demands retribution – the God who requires the shedding of blood for the forgiveness of sins.

Thankfully these days there’s an emergent form of Christianity – one that does not buy this “blood atonement theory” – and it is a theory. Today, more and more Christians are saying they do not believe that God requires the shedding of blood… The point is, violence is not a solution – it’s always a problem. We have to get to see that violence never purifies – it always defiles. In every form it is defiling.

That’s why if Jesus was standing here today, I believe he’d say, “don’t call me the lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world.” He might say rather something more like “I am a window to divinity and a mirror of humanity. What I came to do is to show you what it means to be open to the Divine and to reflect the best of who we are as human beings. And everybody can reflect this and be this window if only we have the spiritual vision to see clearly enough.”

In other words, Jesus, I believe, would not say that he suffered to keep us from suffering – he suffered because to be human is to suffer. Jesus hangs there because life is always hanging in the balance for all of us all of the time.

I was so taken by his willingness to take on the violence inherent in the crucifixion image – and I responded in kind with my remarks:

There’s no getting around it: to observe the Seder, you need to tell a story of oppression and violence. And you cannot get to what is for Christians resurrection and what is for Jews the Exodus from Egypt without going through that moment of violence…

I will also say I share with you, Bob, completely, that I do not view violence in any way as redemptive. I reject that categorically. I think we all have to. But we still have to struggle with the way violence affects us and what it does to us and what it does to our souls. We can’t ignore it. Even if we disavow it, we can’t ignore it.

As a Jew… I fear the violence that is embodied by the Seder and that has been waged against the Jewish people for centuries will turn us into a bitter people. That it will only cause us to have a sense of entitlement which means we use our pain as a weapon against the outside world because nothing we do to anyone else can be nearly as horrible as what’s been done to us. Or it will cause us to build bigger walls between us and the rest of the world and to instill a Jewish identity that basically says nothing more than “all the world really wants us dead, and that’s what it means to be a Jew. And we have to be forever vigilant because we live in a world that hates Jews.”

And while I’m not unmindful of this history and I do think we need to retell this history because those who do not study history are condemned to repeat it…I also think we need to look seriously at what this legacy of violence and oppression does to us and what we do with it.

And for me that means bearing witness to oppression in the world. If there is any sliver of redemption in violence, it means that it can open the door to empathy – and I would suggest that this idea comes from a very deep place in Biblical tradition – in the Torah.

The commandment commanded more times than any other in the Torah is some version of “Do not oppress the stranger because you were once strangers in the land of Egypt.” To me what that says is “you don’t take your pain and use it as a weapon against the outside world. You take your pain and use it as a tool for empathy with the outside world – and to bear witness against oppression no matter where it is fomented, whether it is in our community or it’s in any community.

We cannot hold on to our pain as uniquely ours, and I want to come back to something you said earlier, Bob: “We’re all in this together. It’s not some of us – it’s all of us. And violence against one people is violence against all.”

You can read some of Bob’s thoughts about our service on a piece he’s just written for Examiner.com You can also click below to hear an audio of the entire service. (The service itself begins at the 10:00 point).