I’ll be honest with you: I never liked High Holiday services when I was a kid.

There were so many things that just rubbed me the wrong way: they felt interminably long, the old school Reform choir music wasn’t my thing, and my parents would constantly shush me and my brothers when we got squirrelly (which was often). But most of all, I resented the seeming irrelevance of it all. I just couldn’t relate to the content of the services – and there was never any effort to explain why it should be relevant to me.

On Rosh Hashanah in particular, I just couldn’t relate to the constant stream of prayers singing God’s praises, extolling God’s greatness and invoking God’s power. It all seemed designed to make us feel small and insignificant: this repeated glorification of an all-powerful God to whom we must beg and plead for another year of life.

I realize now that I was a pretty astute kid. “Malchuyot,” which literally means “sovereignty,” is one of the central themes of Rosh Hashanah. Every new year we declare over and over that God is our supreme ruler. This theme is repeated throughout the liturgy, particularly during the Musaf service, when it is traditional to physically prostrate oneself on the floor before the divine throne during the Aleinu prayer.

Over the years, however, as I began to attend services on my own terms rather than under duress, I came to appreciate Rosh Hashanah, yes, even the idea of Malchuyot. In fact, the older I get, the more relevant and important this concept feels to me. On a personal level, I understand to be a Malchuyot is a reminder that we often labor under illusions of our own power and control. We face these illusions head on during Rosh Hashanah when we do the work of teshuvah: the sacred process of return and repentance.

Of course, we are not all powerful. But ironically, acknowledging the limits of our power can actually be liberating. By affirming a transcendent source of power greater than our own, we can better focus and identify the things we can control in our lives. When we invoke God’s Malchuyot on Rosh Hashanah, we do so in the spirit of this liberation, to break free of our illusions of power and put ourselves on a more productive, healing path during the Days of Awe.

Beyond the personal, I’d suggest Malchuyot has a collective and political dimension as well. It’s deeply rooted in Judaism’s central sacred narrative, the Exodus story. I actually made this very point during my very first sermon for Tzedek Chicago on Rosh Hashanah ten years ago:

At its core, I would suggest affirming Malchuyot means affirming that there is a Force Yet Greater: greater than Pharoah in Egypt, greater than the mighty Roman empire, greater than the myriad of powerful empires that have oppressed so many peoples throughout the world.

I would argue that this sacred conviction has been one of the central driving forces of Jewish tradition throughout the centuries: that it is not by might and not by power – but by God’s spirit that our world will ultimately be redeemed. I would further argue that this belief in a Power Yet Greater has sustained Jewish life in a very real way. After all, the Jewish people are still here, even after far mightier empires have come and gone. It might well be said that this allegiance to a Power Yet Greater is the force that keeps alive the hopes of all peoples who have lived with the reality of dislocation and state oppression.

I went on to suggest that through Zionism, the Jewish people have tragically betrayed this sacred Jewish narrative of liberation. When you think about it, the raison d’etre of Zionism literally is human sovereignty. It is an ideology that unabashedly deifies state power as a redemptive force in Jewish life and overturns centuries of Jewish tradition. It has subverted the sacred ideal of Malchuyot by centering and sacralizing human power above all else.

When I delivered that first Rosh Hashanah sermon, however, I never could have predicted where Zionism’s bargain with state power would lead us. In the misguided name of Jewish safety and supremacy, Israel has doubled down on its assumption of human Malchuyot to an unbearable degree. As we gather for Rosh Hashanah this year, Israel has been perpetrating an almost two-year genocide against the Palestinian people. Nearly 70,000 Palestinians have been killed, with real numbers likely to reach the hundreds of thousands. Whole families have been killed and entire bloodlines erased. Untold numbers of people have been buried under rubble, burned alive, dismembered and starved to death. At this very moment, Israel is literally bombing the entire north of Gaza off the map, trapping scores of residents who cannot leave their homes and sending scores of others to the south into active war zones.

And yet of course. Of course it has come to this. From the very beginning, the goal of establishing a Jewish-majority nation state could only be realized by dispossessing another people – what the Palestinian people refer to as the Nakba. Israel’s genocide against the Palestinians did not begin on October 7; it has been ongoing for over 70 years. There is a direct line leading from Zionism’s idolatrous attachment to Malchuyot to the crimes we are witnessing daily in Gaza.

This idolatrous attachment, of course, is not unique to Zionism. Looking back, I realize that Tzedek Chicago’s first Rosh Hashanah service took place shortly after Trump announced his first Presidential campaign. It’s also fair to say when I gave that first sermon, I never would have dreamed that just ten years later, the US would be rapidly descending into authoritarian fascist rule. That ICE would serve as our President’s secret police force, prowling the streets in plain clothes and face masks, abducting immigrants and student activists in unmarked vans. That thousands of National Guard troops would be mobilized to occupy American cities. That so many of our nation’s institutions would be defunded, plundered and centralized by unelected oligarchs. That our government would openly declare whole groups of people, including immigrants, trans people, people of color and unhoused people to be literal “enemies of the state.”

In the wake of Charlie Kirk’s murder, the incitement against these imagined enemies has reached a terrifying fever pitch. Trump and the movement he spawned are now seizing this moment to foment fury against a broad array of individuals and institutions they call the “radical left.” Trump’s aide Stephen Miller has chillingly characterized the current moment in America as a battle between “family and nature” and those who celebrate “everything that is warped, twisted and depraved.”

Words such as these should not sound new to us; the Trump regime is using a time-honored tactic from the fascist playbook. We know that totalitarian regimes have historically consolidated their power during times of instability by fomenting a toxic “us vs. them” narrative. Hannah Arendt identified this mentality very clearly seventy-five years ago in her book The Origins of Totalitarianism: “Tribal nationalism always insists that its own people are surrounded by a ‘world of enemies’ – one against all – and that a fundamental difference exists between this people and all others.”

Although the context of 21st century fascism is different in many ways from fascisms of the past, the fundamental building blocks of this phenomenon remain the same. In the parlance of Rosh Hashanah, the fascists of today are claiming Malchuyot – ultimate power – for themselves. And they are consolidating their power by demonizing those who do not fit into their idealized, privileged group as enemies who must be fought and eradicated at all costs.

However, as overwhelming as the current political moment might feel, there is a textbook for resisting fascism as well. The essential rules for fighting fascism remain the same as they ever were. And the first order of business is: do not collaborate.

This may seem obvious, but given the hard truth of the moment, I don’t think it can be repeated enough. It has been truly breathtaking to witness how quickly ostensibly independent non-governmental institutions have capitulated to Trump’s bullying and blackmail: from universities firing professors and defunding whole programs to businesses eradicating their DEI programs; from corporate media outlets becoming state mouthpieces, to law firms allocating hundreds of millions of dollars in legal services to defend the federal government.

Has the liberal establishment been up to the challenge of this moment? Just consider its response to the murder of Charlie Kirk. Let’s be clear: Kirk was an unabashed white Christian Nationalist who incited young people on college campuses to hatred under the cynical pretense of “open dialogue.” Even so – and even as the MAGA movement is dangerously exploiting this moment – liberal leaders and institutions have been normalizing Kirk by openly praising him as a paragon of free speech and good faith debate.

After he was killed, CA Governor Gavin Newsom eulogized Kirk by saying: “The best way to honor Charlie’s memory is to continue his work: engage with each other, across ideology, through spirited discourse. In a democracy, ideas are tested through words and good-faith debate.” Similarly, following Kirk’s murder, the Dean of Harvard College, David J. Deming publicly vowed to protect conservative students on campus, adding that Kirk’s enthusiasm for publicly debating his opponents could be a model for Harvard’s own civil discourse initiatives. And for his part, liberal New York Times columnist Ezra Klein wrote an op-ed entitled “Charlie Kirk Practiced Politics the Right Way.”

It’s not clear if these apologists honestly believe what they are saying or if they’re just trying to avoid the government’s takedown of anyone who has anything remotely critical to say about Charlie Kirk. But in the end, it really doesn’t matter. The bottom line: liberal normalization will not appease fascists.

To put it frankly, the government has declared war on us – and we must respond accordingly. The days of partisan cooperation and dialogue are over. The days of good faith debate and civic compromise are over. Capitulating to demagoguery and hatred will not convert the MAGA movement to the values of democracy and civil discourse. Yes, in a healthy democratic society, the concept of “collaboration” is something to be valued. But in a fascist regime, the term “collaborator” has a different meaning entirely.

The first step in resisting collaboration is to accept that none of this is normal. We must let go of old assumptions, many of which, frankly, have led us to this moment. If we are to be totally honest, it must be said that the Democrats and the liberal establishment have been collaborating with corporate interests along with Republicans for years. As we interrogate the abnormality of this moment, we must admit that the entire system has been disenfranchising whole groups of people in this country for far too long.

Resisting fascism also means letting go of our ultimate faith in the “rule of law.” Indeed, both the left and the right tend to fetishize the rule of law as an absolute good. And while it’s true that the law can be a tool to ensure a more just society, it can just as often be used as a blunt instrument to dismantle democracy.

We know from history that governments routinely create laws that are inherently unjust. Slavery was legal in the US for almost 250 years. Apartheid in South Africa was legal. Apartheid continues to be legal in Palestine/Israel. In the face of such legal injustice, the obvious moral and strategic response is not to follow but to break the rule of law. As Dr. Martin Luther King famously wrote in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail:”

We should never forget that everything Adolf Hitler did in Germany was “legal” and everything the Hungarian freedom fighters did in Hungary was “illegal.” It was “illegal” to aid and comfort a Jew in Hitler’s Germany. Even so, I am sure that, had I lived in Germany at the time, I would have aided and comforted my Jewish brothers.

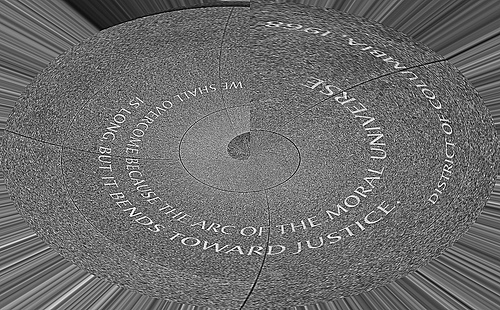

This is, in fact, the radical truth we affirm every Rosh Hashanah. When we affirm Malchuyot, we affirm that there is a moral law yet greater than any law levied by a government or regime. On this Rosh Hashanah in particular, the sound of the shofar calls on us to resist conformity; to vow to become criminals when confronted with laws that are inherently unjust. More than any Rosh Hashanah in our lifetimes, we must be ready to defy the illegitimate laws wielded by the illegitimate rulers who would govern us.

Even if we do accept this challenge, however, the question remains: where does Malchuyot, ultimate Power, reside, if not with governments, politicians or the rule of law? Here, I’d like to quote yet another one of my heroes, the Puerto-Rican Jewish liturgist Aurora Levins Morales:

They told me we cannot wait for governments.

There are no peacekeepers boarding planes.

There are no leaders who dare to say

every life is precious, so it will have to be us.

Yes. God’s power is revealed in our readiness to show up for one another. When we acknowledge Malchuyot on Rosh Hashanah, we affirm that the Divine Presence is manifest whenever we struggle and resist and fight for our communities, for a world where all are liberated and cherished and protected. When there are no leaders who dare to ensure that every life is precious, it will have to be us.

Here are two concrete examples of Malchuyot in action: this last January, shortly after the inauguration, the Trump administration launched a series of raids in Chicago they called “Operation Safeguard” where, over the course of a few days, ICE, the FBI, the ATF and other federal forces coordinated massive raids in neighborhoods throughout the city and suburbs. We don’t know how many were arrested or detained, but we do know that this federal blitzkrieg was deeply frustrated by local organizing. Trump’s so-called “border czar” Tom Homan later complained that immigration organizers in Chicago were “making it very difficult” to arrest and detain people. He said, “They call it Know Your Rights. I call it how to escape from ICE.”

Of course, even as we win these battles, this fierce war continues to escalate. ICE violence continues to rage in the neighborhoods of our cities. In Chicago, ICE has now launched another sweep, this one called “Operation Midway Blitz.” Just last Friday, at an immigrant processing center in the Broadview section of Chicago, federal agents shot tear gas, pepper spray and flash bang grenades into hundreds of demonstrators. Ten protesters were taken into custody by federal agents over the course of the day. Even amidst this escalating violence, however, local organizers here in Chicago continue to hold the line.

Another example: in Washington DC which is still under occupation by National Guard troops, groups of local residents called “night patrols” have been regularly patrolling the streets. According to journalist Dave Zirin, whose reports from the ground have become invaluable:

These night patrols watch over the city to ensure that people are protected from state violence, false arrest, abduction, and harassment. Failing that, their goal is to document the constitutional violations or brutality they witness, so people can see the truths about the occupation that a compliant, largely incurious media are not showing.

Critically, these neighborhood patrols are being led and stewarded by members of impacted groups: As one night patroller put it: “a lot of young people, a lot of people of color, queer and trans folks, people who have been directly impacted by policing, and folks with street medic backgrounds. It skews toward people who already know what it’s like to be criminalized.”

Though it isn’t being highlighted by the corporate mainstream media, this local organizing is happening in communities all over the country: in Los Angeles, where there are also still hundreds of National Guard troops, as well as New Orleans, Memphis, Baltimore and other cities that the Trump administration is directly threatening with military invasion. I know that many Tzedek Chicago members have long been active in these organizing efforts, here in Chicago, around the US and even around the world. But again, we can have no illusions over what we are up against.

I know that the magnitude of these events often leads us to a state of overwhelm and despair. We doom-scroll through the news every day, we read about Trump’s newest executive order, the latest regressive Supreme Court ruling or some other heinous event and the ferocity of this onslaught can literally leave us breathless. This is, of course, yet another page from the authoritarian textbook: to neutralize the population through a calculated strategy of shock and awe. They want us to feel that all is lost, to give in to our despair that their power over us is all but inevitable.

Our experience of shock and overwhelm is compounded all the more by an all-pervasive sense of grief. So much of what we have fought for has been lost. So many of the institutions we assumed would be eternally with us are being plundered and dismantled. Some of these losses may be permanent, some may not, but the harms they are causing are very, very real.

I feel this grief myself, believe me, I do. But I also know that if we surrender to it, then their victory over us will become self-fulfilling. The way through the fear and the grief, I truly believe, is to never forget that we have power, that our words and actions matter and that nothing is ever inevitable unless we let it be so.

Whenever we feel overwhelmed, I think the critical first step is to reclaim our equilibrium by asking ourselves, what matters most to me? What are the issues that are nearest to my heart? Most of us have the capacity to devote our time and energy to one or two causes at most. What are the most effective organizations fighting for this cause? Who are the people in my life that can connect me with the people doing this work? If I don’t have the capacity or physical ability to engage actively in these kinds of responses, what are other meaningful ways I can show up?

Amidst all this loss, we must never forget: even if our victory is not guaranteed, there are still things in this world worth fighting for. Generations of resisters have understood this axiom well: “If I’m going to go down, I’m sure as hell going to go down swinging.” In the words of my friend and comrade, Chicago organizer Kelly Hayes, who I’ve quoted in more than one High Holiday sermon over the years:

I would prefer to win, but struggle is about much more than winning. It always has been. And there is nothing revolutionary about fatalism. I suppose the question is, are you antifascist? Are you a revolutionary? Are you a defender of decency and life on Earth? Because no one who is any of those things has ever had the odds on their side. But you know what we do have? A meaningful existence on the edge of oblivion. And if the end really is only a few decades away, and no human intervention can stop it, then who do you want to be at the end of the world? And what will you say to the people you love, when time runs out? If it comes to that, I plan on being able to tell them I did everything I could, but I’m not resigning myself to anything and neither should you. Adapt, prepare, and take the damage done seriously, but never stop fighting. Václav Havel once said that “Hope is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something is worth doing no matter how it turns out.” I live in that certainty every day. Because while these death-making systems exist both outside and inside of us, so do our dreams, so long as we are fighting for them. And my dreams are worth fighting for. I bet yours are too.

This New Year, I realize I’ve come a long way from that beleaguered kid who felt disempowered on the High Holidays to a rabbi telling you Rosh Hashanah is our clarion call to fight facism. But here I am. And here we are. May this new year inspire us all with the knowledge that true sovereignty, true Malchuyot, lives at the heart of the struggle.

On this, my final Rosh Hashanah with this amazing community, this is what I am feeling to my very bones at this moment: that while Pharaohs may rise, they will inevitably fall, that beyond the horizon of Olam Hazeh, this terribly broken world, there lies Olam Haba: the world we know is possible. And no matter what may happen this new year – and every new year to come – that world is always worth fighting for.

Shanah Tovah.