There’s been a great deal of analysis written about German writer Gunther Grass’ now-infamous new poem, “What Must Be Said” (in which Grass criticized Israel’s nuclear program as endangering an “already fragile world peace.”) For me, the most astute response by far comes from Mideast historian Mark LeVine, writing in Al-Jazeera.

LeVine skillfully parses the psychology and the politics behind the uproar – but it is his identification of the larger context of the issue that resonates most powerfully for me. Here’s a long excerpt from a much longer article. The entire piece is well worth reading:

Israel has always sought to portray itself as a “normal” country, yet goes out of its way to ensure no one “names it” – to use Grass’ words – as what it is, a colonial state that every day intensifies its occupation of another people’s land. And so Grass has taken it upon himself to “say what must be said”, to name Israel as what it is, a “nuclear power” that “endangers the already fragile world peace”. It’s worth noting he doesn’t even mention the occupation, which is the far greater threat to world peace.

I have no idea if Grass really believed himself to be “bound” to Israel; if he did, we can imagine the bond is broken today, at least by Israel, now that he’s banned from returning. But Grass’ feelings are not what’s interesting or important. What’s important is the larger context, all the other “facts” which refuse to be accepted as “pronounced truths”.

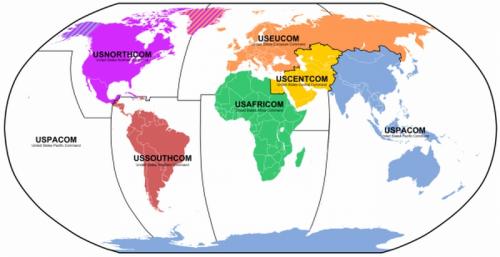

These facts are that Israel, however egregious its crimes – and anyone who denies them is either completely ignorant or a moral idiot – is but one cog in a much larger global machine, one that includes too many other cases of occupation, exploitation, and wanton violence to list comprehensively here (we can name a few – Syria, China, Russia, India, Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Bahrain, Uzbekistan, Sri Lanka, the Congo, and of course, NATO and the United States – whose oppression, exploitation, and murder of their own or other peoples is a far more concrete “fact” than the potential for mass destruction caused by Israel’s nuclear programme)…

The larger fact is that the global economy is addicted to war, to militarism, oil and the rape of the planet for the minerals and resources that fuel the now globalised culture of hyperconsumption that will doom our descendants to a fate we dare not contemplate. Israel’s gluttony for Palestinian territory, and its willingness to encourage a regional nuclear arms race to keep it, is ultimately no different than the the gluttony for the 60-inch TV, the iPhone/Pad, the cavernous homes and cars, the ability to live at levels of consumption that are only sustainable if most of the world lives in poverty that increasingly defines all our cultures.

Israel has gotten Palestine on the cheap, and it costs relatively little to continue the occupation. Far less than it would cost to end it. So why bother? Especially when everyone else is doing, more or less, the same thing and, it’s clear, no one really cares anymore. Germany, whose remarkable economic stability in the recent global financial crisis is in good measure due to its central role in this global economy of hyper-consumption (think of all the energy and resources that go into making and driving all those fancy German cars), is certainly playing its role all too well.

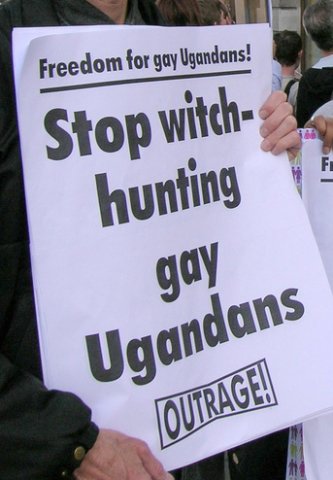

If Grass is right that we must talk about the threat to world peace posed by Israel’s nuclear programme – and far more by its ongoing occupation – then we must also talk about the threat to global peace posed by the sick global system of which Israel is merely one of the more easily identifiable symptoms. Unlike my parents, I’m happy that Germans finally feel secure enough publicly to speak critically about Israel. But if they want their words to have a chance of bringing about a change in its behaviour, they, and everyone else, needs to broaden the discourse to include their own role in enabling and profiting from the system that Israel’s actions so benefits, and the global scope of the victims it daily produces.

Of course, this discourse would require a much longer and more complex poem, written by an even better poet than Grass. If someone manages to write it, I hope it will get the same publicity as “What Must Be Said”.