I’ve decided not to celebrate Yom Ha’atzmaut today. I don’t think I can celebrate this holiday any more.

That doesn’t mean I’m not acknowledging the anniversary of Israel’s independence – only that I can no longer view this milestone as a day for unabashed celebration. I’ve come to believe that for me, Yom Ha’atzmaut is more appropriately observed as an occasion for reckoning and honest soul searching.

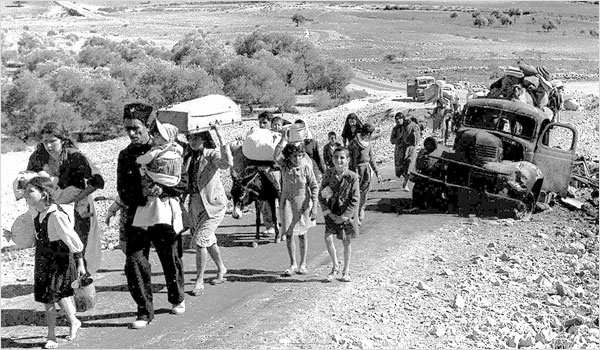

As a Jew, as someone who has identified with Israel for his entire life, it is profoundly painful to me to admit the honest truth of this day: that Israel’s founding is inextricably bound up with its dispossession of the indigenous inhabitants of the land. In the end, Yom Ha’atzmaut and what the Palestinian people refer to as the Nakba are two inseparable sides of the same coin. And I simply cannot separate these two realities any more.

I wonder: if we Jews are ready to honestly face down this “dual reality” how can we possibly view this day as a day of unmitigated celebration? But we do – and not only in Israel. Indeed, there is no greater civil Jewish holiday in the American Jewish community than Yom Ha’atzmaut. It has become the day we pull out all the stops – the go-to day upon which Jewish Federations throughout the country hold their major communal Jewish parades, celebrations and gatherings.

I wonder: how must it feel to be a Palestinian watching the Jewish community celebrate this day year after year on the anniversary that is the living embodiment of their collective tragedy?

I can’t yet say what specific form my new observance of Yom Ha’atzmaut will take. I only know that it can’t be divorced from the Palestinian reality – or from the Palestinian people themselves. Many of us in the co-existence community speak of “dual narratives” – and how critical it is for each side to be open to hearing the other’s “story.” I think this pedagogy is important as far as it goes, but I now believe that it’s not nearly enough. It’s not enough for us to be open to the narrative of the Nakba and all it represents for Palestinians. In the end, we must also be willing to own our role in this narrative. Until we do this, it seems to me, the very concept of coexistence will be nothing but a hollow cliche.

Toward a new understanding of Yom Ha’atzmaut, I commend to you this article by Amaya Galili which was published today in the Israeli newspaper Yediot Achronot. Galili is affiliated with Zochrot – the courageous Israeli org that works tirelessly to raise their fellow citizens’ awareness about the Nakba.

An excerpt:

The Israeli collective memory emphasizes the Jewish-national history of the country, and mostly denies its Palestinian past. We, as a society and as individuals, are unwilling to accept responsibility for the injustice done to the Palestinians, which allows us to continue living here. But who decided that’s the only way we can live here? The society we’re creating is saturated with violence and racism. Is this the society in which we want to live? What good does it do to avoid responsibility? What does that prevent us from doing?

Learning about the nakba gives me back a central part of my being, one that has been erased from Israeli identity, from our surroundings, from Israeli education and memory. Learning about the nakba allows me to live here with open eyes, and develop a different set of future relationships in the country, a future of mutual recognition and reconciliation between all those connected to this place.

Accepting responsibility for the nakba and its ongoing consequences obligates me to ask hard questions about the establishment of Israeli society, particularly about how we live today. I want to accept responsibility, to correct this reality, to change it. Not say, “There’s no choice. This is how we’ve survived for 61 years, and that’s how we’ll keep surviving.” It’s not enough for me just to “survive.” I want to live in a society that is aware of its past, and uses it to build a future that can include all the inhabitants of the country and all its refugees.

Click here to read the article in the original Hebrew. Click below to read the entire English version. (Heartfelt thanks to my friend Mark Braverman for sending it along.)

Identity Card

“Where will you be for the holiday? Are you going to the celebrations in town? To a picnic in the Carmel Forest? It’s really beautiful there! Won’t you come? Everyone’s going.” A few years ago I would have joined them; a picnic out in the country – what could be wrong with that? But something changed. People around me are celebrating, but I’m not.

Once, at one of the picnics, I came across the remains of an old building with a blue dome. I discovered that it had belonged to the village of Ein Ghazal. IDF soldiers expelled its Palestinian residents on 26.7.1948, Israel prevented them from returning, and planted the Carmel Coast Forest among the ruins of the buildings it demolished. It was difficult to see the remains, but once I did I could no longer ignore them – the ruins of villages where people lived until 1948.

The nakba (which means “great catastrophe” in Arabic) began in 1948, when the Zionists began to expel most of the Palestinian inhabitants, to demolish their homes and erase the rich Palestinian culture. The nakba continues today with destruction of Palestinian buildings, mosques and cemeteries, expropriation of land for the benefit of Israeli Jews, institutionalized discrimination, refusal to allow Palestinian refugees to return home, military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, systematic killings in Gaza, most of whose residents are refugees, and more. We don’t want to see or hear any of this, and certainly not on Independence Day.

As I spoke with people about the nakba, and learned more about it, I began to ask myself questions and began to get worried. A crack opened in what I had known, and in my identity. The crack made me continue questioning. This educational process allows me to rethink my life here. The nakba isn’t only the Palestinian’s memory and history. It’s also an event that is a part of my individual and collective memory and identity as an Israeli.

The Israeli collective memory emphasizes the Jewish-national history of the country, and mostly denies its Palestinian past. We, as a society and as individuals, are unwilling to accept responsibility for the injustice done to the Palestinians, which allows us to continue living here. But who decided that’s the only way we can live here? The society we’re creating is saturated with violence and racism. Is this the society in which we want to live? What good does it do to avoid responsibility? What does that prevent us from doing?

Learning about the nakba gives me back a central part of my being, one that has been erased from Israeli identity, from our surroundings, from Israeli education and memory. Learning about the nakba allows me to live here with open eyes, and develop a different set of future relationships in the country, a future of mutual recognition and reconciliation between all those connected to this place.

Accepting responsibility for the nakba and its ongoing consequences obligates me to ask hard questions about the establishment of Israeli society, particularly about how we live today. I want to accept responsibility, to correct this reality, to change it. Not say, “There’s no choice. This is how we’ve survived for 61 years, and that’s how we’ll keep surviving.” It’s not enough for me just to “survive.” I want to live in a society that is aware of its past, and uses it to build a future that can include all the inhabitants of the country and all its refugees.

Recognizing and implementing the right of return are necessary conditions for creating that future. The refugees’ right of return is both individual and collective. Return does not mean more injustice and the expulsion of the country’s Jewish inhabitants. As has occurred elsewhere in the world, ways can be found to implement the return of the refugees without expelling the country’s current residents. That’s what should happen here, and it’s possible. Implementing the right of return will allow us, Jewish Israelis, to end our tragic role of occupiers.

Life doesn’t have to be a zero-sum game. There are other alternatives. Palestinians and Jews can together build a society that is just and egalitarian. People will live sanely, not perpetually anxious and in fear of war. And then? Then we’ll really have a happy holiday.

Amaya Galil

Zochrot

Translation: Charles Kamen

Thank you for this, Brant, and it’s hard to convey how deeply I mean that. What you have expressed here gives me hope – and it’s hard to convey how much it means to say that in the midst of the pain and the despair and horror that I have felt in the situation in which we find ourselves. Taking in and taking on the condition of the Palestinian people is the only way through to whatever lies beyond the current condition of war, separation, and spiral of violence. And you are so right: it is not about “two narratives,” or “interfaith” or “intercultural” understanding. No — in order to understand ourselves, what we have done, and what we are doing, we have to understand the experience of the other and fully see and accept our responsibility. And if the other side bears any responsibility, that is for them to understand and deal with. It has no bearing on our responsibility for ourselves. Yom Ha’atzmaut, in order to have any meaning at all, must be devoted to heshbon hanefesh — a self-accounting. And the day before Yom Ha’atzmaut, and the day after, and every day, until we find ourselves clearly and squarely on the path of taking responsibility for what this state has cost.

The tragedy of Israel is precisely what Amaya has expressed. Israeli society is saturated with violence and racism. If this were not so, how could a young Israeli like her say such a thing? If you go to Israel and look below the surface, and ask the questions, and really take a look, this is what you see. It is the Jews that are the true prisoners behind the wall, because it is we who have built that wall. The physical wall exists in Israel. The wall of denial and fear is what we live behind here in the U.S.

It’s easy for me to say these things and write these things, Brant. For you it’s a different story. Thank you for your courage. It’s important. It means a lot.

The day after we met in Chicago last week, I sat in the WBEZ studio and with my colleague Bill and my friend Daoud Nassar from Palestine and taped an interview on Worldview. The interviewer asked me, clearly referring to my Jewish identity, how I came to this work and how it was playing in my Jewish community. I was able tell him a positive story in response to the question — for the first time in the four years I have been involved in this work. I said — there are Rabbis who are now able and willing to seriously — fundamentally — question what we are doing with our Jewish State project. And that this willingness to confront this question was growing, and that it gave me hope. Not for the Palestinian people — they know how to survive and they will survive. It gives me hope for my own people, and for our American society, which is recognizing its complicity in this crime. I used to say: we Jews will be the last, kicking and screaming – who will open their eyes to the truth and join the struggle for a just peace. I now am beginning to believe that perhaps my own people will join the community of Americans, Israeli peace activists and internationals who are mounting this broad movement. I am beginning to think that perhaps I will not have to remain in exile from Am Yisrael.

Mark

Thanks, Brant.

Thanks Brant. The Amaya Galil peace does inspire some hope in a bleak situation.

Just adding to the list of recommended reading, here is a Yom Ha’atzmaut piece by Shulamit Aloni unambiguously stating, “Israel is not a democratic state.”

http://haaretz.com/hasen/spages/1082174.html

Thank you so much for this blog. I’m an (older) rabbinic student at Boston’s Hebrew College and found myself avoiding the school’s celebrations this week. I knew why, but I also felt uncomfortable doing so: after all, it’s not like I hate Israel, just the way many in government and among the citizenry conduct themselves. Your saying that , “Yom Ha’atzmaut is more appropriately observed as an occasion for reckoning and honest soul searching” gave me the balance I was looking for, and I will work during the next year to try to re-direct the school’s celebrations to just this kind of discussion.

This year I marked Yom Haatzma’ut by going to a screening of Waltz with Bashir with the adult ed class I teach at the synagogue. It seemed entirely appropriate to the day: an intense struggle to come to terms with being an unwitting (perhaps) perpetrator in another’s destruction. I was struck that the filmmaker “went there” and connected standing outside the massacre in the Lebanese camps to standing outside the walls of the Warsaw Ghetto. We had a good conversation over drinks afterwards but next time I see it with a synagogue group I hope to have more of a “right wing” presence to really amp up the debate.

Thanks so much having the courage to post this, Brant. While I was living in Washington, DC for the last few years, my close friends and I never affiliated with a synagogue and instead formed our own independent minyan – in part because we felt so alienated by the complete lack of dissent or meaningful discussion about Israel within the organized Jewish community. But I’ve followed and forwarded your blog postings for years because I find them so heartening and truly brave. The discussion your prompt makes me feel like there may actually still be a place for me and my views within the institutional Jewish Community. I’m really proud that you are my home-town Rabbi.

Thank you again,

Evin

Thank you, Brant!

It was odd this week, walking around school where all of my Jewish friends seemed so excited about a holiday that I never really understood. Israel and independence never seemed to go together completely in my mind (in more ways than one) and it is apparent that Israel still has a long way to go before it can be considered so. Yom Ha’atzmaut is less of a celebration for me than it is a reminder of how much there is left to be done in Israel and the Middle East, and how we as American Jews can help Israel to grow in better, more peacful ways.

Kelsey

Revisionist history. Classic Jewish guilt. Self-loathing. And, most important of all – a complete lack of faith that the way Israel exists today is because of Hashem.

The Arabs that chose to stay in Israel have been treated fairly. The Arabs that left have chosen to vote into power a terrorist organization that seeks the destruction of your brother, your sister, your mother, your father, and you.

Israeli independence was nothing short of a modern day miracle and to temper one iota of gratitude to Hashem with concern for those that would seek to kill us is an absolute affront.

How soon we forget our history and how we were exiled, persecuted, burned at the stake, buried alive, and our women were defiled. After the shoah, we were grateful to have a land when no one else would take us in. A land where a few of us had lived for countless centuries. And what was the response of the Arab neighbors when we began to get off the boats with nothing but faded pictures of the gassed and cremated families and friends we left behind? THEY ATTACKED US LIKE AMALEK DID AFTER THE EXODUS.

We are the light and the prism through which Hashem’s light shines into the darkness of this world. The forces of darkness seek to destroy us. It was a miracle that a group of Holocaust refugees could defeat so many armies from so many nations.

We celebrate the miracle because for thousands of years, none of our great grandparents thought it could happen that we would have Israel back. They prayed for it all their lives while living in ghettos and disgusting shtetls and bizarre lands far from their true home. And their prayers paid off and we got Israel back because Hashem heard us. And now, you less than fully grateful Jewish grandchildren temper your gratitude with feelings of sympathy for the people that attacked us. Shame on you. How could you look your Great Grandmother, who risked her life to blow up bridges so the tanks of the enemy couldn’t destroy her new home, in the eye? What would you say to her? That times have changed? That it’s ok to ignore the miracle that she not only survived but set up the only democracy in the Middle East?

I love all of you, my Jewish brothers and sisters, but you have to open your eyes and understand that we must be strong because that is all Amalek and his decendants will ever understand. And please – never, ever dismiss or diminish the power of a miracle from Hashem. Ingratitude will negatively impact all of us.

Let me just second what Evin said: Brant, you make some of us feel at home, Jewishly, for the first time in ages. Deep thanks.

Brant, you are on to something here! It’s time to change the way we celebrate anything, if we want to stay true to our Jewishness.

I’d rather be… well, neither a hammer, nor a nail.

But this world doesn’t give me that option.

All I can hope for is to be a fair or humane hammer, but I don’t even call the shots on that one.

Americans didn’t call the shots about what kind of hammers we were in Iraq, Guantanamo, and many other places along the 200+ years of independent nationhood. Because our government didn’t ask us for our opinions. Nor did it share with us all the awful stuff it did in our name… to support our “way of life”.

Americans celebrate their Independence Day in spite of the great Nakba to the Native Americans who were slaughtered and driven from their lands.

Jews celebrate Passover in spite of all the widows left behind after Pharoh’s soldiers drowned in the sea, and in spite of the horrendous Nakba that ultimately followed the that exodus forty years later on all the innocent dwellers of Canaan.

Brant, I truly appreciate your thoughts and opinions. I am not trying to argue or oppose them. But I feel the need to expand on them a bit.

For each part of our lives we celebrate, there is a victim. Be it the wild life that’s being destroyed by humanity, or the domestic animals being cruelly raised and slaughtered to support our lives. Be it the the people in far away lands, working hard, for pennies, exposed to poisons and other health hazards to support our way of life (like thousands of Chinese workers who get severe mercury poisoning in factories producing CFLs – yes, the hailed environmental “green” light bulbs!); and these are just some tiny examples – the very tip of the massive iceberg.

Our grandchildren and their grandchildren will surely pay the price for our and our parents and grandparents generations’ poor stewardship of this planet (let’s not kid ourselves – no matter how “green” we try to be, we are still driving this planet down the drain – perhaps slower than our parents’ generation, but there are more of us doing it than they were!). And when the sea level rises, it will not discriminate: Tel-Aviv, Gaza, New York… perhaps half the world’s population, if not more, will be driven out of their homes, and dry land will be oh so much more crowded than can even be imagined today… will that be the cause of unfathomable wars?…

Yes, whenever and whatever we celebrate, we should always remember that someone else, somewhere, either paid, is paying, or will pay the price, for our lives, and our celebrations. Because this world gives us no choice – either be the hammer, if you were born on the side of the hammers, or give it up, and become a nail. Unfortunately, we can’t choose to be neither!! And although our Jewish tradition didn’t tell us to always think of the nails when we celebrate our victories, perhaps it’s time to start a new tradition, and include the thoughts about the victims whenever we celebrate our… well, anything in life.

Wouldn’t your reasoning for not “celebrating” Israel Independence Day also preclude “celebrating” American Independence Day?

Isn’t it also the “honest truth” that the founding and growth of the United States of America “is inextricably bound up with its dispossession of the indigenous inhabitants of the land”? What will be the new form of your observance of American Independence Day?

Is there no ethical rationale for the existence of the State of Israel? It seems that’s where you are heading.

I’ll never get there.

Boris,

I’m not sure that the American Independence Day and Yom Ha’atzmaut are so historically comparable. If we’re going to look for parallels, it’s probably more apt to compare Yom Ha’atzmaut to Thanksgiving (inasmuch as it also involves the acquisition of a land at the expense of its indigenous peoples.)

And here I would say yes, we Americans would probably do well to consider T’giving to be a day of reckoning (and not simply a day to stuff our faces and watch football.) I wonder how many Americans actually know that most Native Americans consider this to be an official day of mourning – check out this link for instance: http://www.pilgrimhall.org/daymourn.htm

You ask, “is there no ethical rationale for the existence of the State of Israel?” To be honest, I don’t believe that any nation can ultimately claim an “ethical rationale” for its existence. Nationalism is by its very nature an ethically messy business. At best, one might claim it’s a “necessary evil” but I personally struggle with even that.

It’s worth pointing out that Jews have been the victims of other nationalistic movements for centuries. Now that we’ve gotten into the nationalism business ourselves, it would behoove us at least to seriously consider what we’ve wrought before we break out the party hats.

Rabbi Brant,

A few weeks ago, I went on a trip to Bethlehem. We visited various Palestinian institutions and met with different groups. I learned that the Nakbah is central to their identity, and that they do see themselves as victims.

That said, I celebrated Yom Ha’atzma’ut. I’m in Israel right now. I danced in the streets at night and in the morning, I attended two barbeques. I prayed festively with better kavanna than I have ever had.

I recognize that the founding of Israel is tied to suffering. I can even take responsibility for that suffering. But I refuse to muffle my emotions.

I am ecstatic that there is a state of Israel, a country that I can call home. I am ecstatic that the hundreds of thousands of Jews who were in this country in 1948 were not slaughtered by the incoming Arab armies. (Do you have any doubt that that would have been the result had Israel lost?) I sit at my computer looking over the beautiful Jezreel Valley and know that what happened in 1948 is responsible for my safety and ability to take advantage of my spiritual homeland.

I will not argue that Israel has committed sins in the past. I’m not suggesting that we can’t represent with the Palestinians in their suffering. I’m not suggesting that we shouldn’t help them. But I am saying that we have every right to rejoice in our freedom. Even if the creation of the state is inextricably bound with suffering, it was created in a war! Wars are the definition of suffering. I suggest you stop celebrating Hanukah, Purim, Pesach, and Veterans DAy. Your claim that your values only restrict holidays based on land being taken is rather absurd. People suffer for other reasons.d

The Jewish people have a state, something we haven’t had for two thousand years. I’m happy, and I wish you were, too.

Richard

Rabbi Brant, I can understand your not wanting to celebrate Yom Ha’atzmaut. You recently wrote in your April 22, 2010 post: “I am having a increasing difficult time getting past the fact that our Jewish national rebirth has come at the expense of the Palestinians.” That is a historical fact that our people have yet to acknowledge. You are contributing by creating awareness of this fact which I appreciate greatly.

Would you consider commemorating Nakba Day (each May 15th) as a way to mourn and repent the injustices our people committed? If so, would you consider celebrating Yom Ha’atzmaut to acknowledge the positive outcomes that Zionism has realized?

Dear Rabbi, How do you feel about the innocent Jews that are killed by the Palestinians? You express their suffering. I was friends with the Fogel family in Israel, I cannot begin to express the pain and the anger that is in my heart because of what they did. How do you excuse their behavior? How do you even call yourself Rabbi Man of G-d. to defend their attacks on Israel. I bet you don’t celebrate Yom Hashoah either because the Palestinians claim that it’s false. I say shame on you sir. These people choose to keep terrorists as leaders, they choose to not do anything good with the resources they have. If you choose not to be Zionist and support Israel that is your choice, then stay out and please don’t spread l’shon Hara!

Today I was searching for images for Yom Ha’atzmaut. I found this piece of filth.

Most of the comments here as well as the author are so full of poo that it makes me want to cry.

YOU are the jews that urged the rest of us to shut up and get on the cattle cars.

I am ashamed of jews like you. Just as you are ashamed of your identity and willing to believe any lie told by our enemies.

WE are the indigenous population.

The only “systematic killings” are that of Jews by their enemies.

Next “Rabbi” (teacher of poop, more like) will you “teach” us to be ashamed on Passover for the killing of christian children, draining of their blood and all the rest of the blood libel?

It is horrible to see how far jews like you will go to believe the big lies. I am SICKENED.