My remarks at a Festshrift in honor of Marc Ellis held at Southern Methodist University, April 14-16, 2018. The gathering included presentations by a number of Marc’s colleagues and friends, including Naim Ateek, Sara Roy, Santiago Slabodsky, Robert O. Smith, Joanne Terrell, Susanne Scholtz, Robert Cohen and Marc’s two sons, Aaron and Isaiah Ellis:

My remarks at a Festshrift in honor of Marc Ellis held at Southern Methodist University, April 14-16, 2018. The gathering included presentations by a number of Marc’s colleagues and friends, including Naim Ateek, Sara Roy, Santiago Slabodsky, Robert O. Smith, Joanne Terrell, Susanne Scholtz, Robert Cohen and Marc’s two sons, Aaron and Isaiah Ellis:

I first learned about Marc Ellis’ book “Toward a Theology of Jewish Liberation” shortly after the first edition was published in 1987. I discovered it quite by accident on the shelf of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College library. Questions abounded: What on earth was Jewish Liberation Theology? And who on earth was Marc Ellis? Like any pretentious young rabbinical student, I thought I knew my contemporary Jewish theologians. Then I saw from the byline that he taught at Maryknoll. Wait, was he even a Jewish theologian?

It took me only a few paragraphs into the book to learn that he was in fact Jewish. As I read on however, it became clear that Marc Ellis was unlike any Jewish theologian I’d ever read. For one thing, he wrote about Palestinians. A lot. He presented Israel’s oppression of Palestinians as theological category. He wrote about the moral cost of Jewish empowerment. He wrote about Jewish collective confession to the Palestinian people. It was radical Jewish theology in every sense of the word.

I wasn’t ready to fully hear what Marc had laid before me at the time. I don’t think I even finished the book. It’s wasn’t for lack of concern for Palestinians – as a liberal Zionist, I had long identified with the Israeli peace movement and had supported Palestinian statehood back when such things were considered beyond the pale by the organized Jewish community. But I would never dare to view Israel’s treatment of Palestinians as a theological concern. Like most liberal Zionists, I viewed the peace process in pragmatic terms. I didn’t necessarily support a two state solution for moral reasons – it was all about Israel remaining “Jewish and democratic.” I also don’t think I would have been too comfortable referring to Israel’s treatment of Palestinians as “oppression.” Like most liberal Zionists, I would have said it was “complicated,” with enough blame to go around.

Over the years however, I struggled with nagging, gnawing doubts over these talking points. Although I was able to keep these doubts at bay for the most part, I was never able to successfully silence them. When I was ordained as a rabbi in 1992, the stakes were raised on my political views. As you know, rabbis and Jewish leaders are under tremendous pressure by the American Jewish organizational establishment to maintain unflagging support for what Marc would later call “Empire Judaism.” Few, if any congregational rabbis would dare cross this line publicly.

I’d been a rabbi for about 10 years when I returned to “Toward a Theology of Jewish Liberation,” which had just been released in a much-expanded third edition. This time I was ready. I read it cover to cover. And this time, Marc’s unflinching moral clarity made a direct line to my head and my heart. Liberal Jewish thinkers typically treated Israel/Palestine as a complex political issue that needed addressing. Marc, on the other hand stated unabashedly that Israel’s oppression of the Palestinians was the issue – the central moral issue facing Jews and Judaism today. All the rest was commentary.

Taking his cue from the Holocaust theologians he analyzed so well in his book, he viewed Jewish empowerment following the Holocaust as a critical turning point in Jewish history. Like them, Marc embraced this empowerment – he had no desire to turn the clock back to an old diaspora of a bygone era. But unlike thinkers such as Irving Greenberg, Richard Rubenstein, et al, he was unwilling to view support for Jewish empowerment – embodied by the state of Israel – as a “sacred Jewish obligation” for the current era. Quite the contrary: if we had any sacred obligation at all, it was to repent and make confession to the Palestinian people for our collective sins against them.

However, there still remained the question: “Who is this guy?” I noticed that he was now teaching at Baylor University and had established its Center for American and Jewish Studies. Of course I understood that someone who espoused ideas such as these wouldn’t necessarily be welcome in Jewish institutional circles – but it was still astonishing to me that his name was not counted among the top Jewish thinkers of our day.

I discovered that he had become quite prolific since the publication of “Theology of Jewish Liberation.” I also discovered that his ideas had deepened and broadened. He had coined terms such as “Constantinian Judaism” and the “Ecumenical Deal.” He wrote extensively about “Jews of Conscience” and the “Jewish Prophetic.” He wrote about the end of ethical Jewish history.

As I personally evolved on the issue of Israel/Palestine, Marc’s work became a central guiding force for me. And while I wasn’t always ready to go to the places he did, it was liberating to know there was someone in the Jewish world who was actually saying these words out loud. More than anyone I had ever encountered, here was someone who embodied the essence of the prophetic. Frankly, liberal Jews had been bandying this word to the point that it has now become an empty cliche. But Marc understood that prophetic meant daring to utter aloud the unutterable.

Of course it also meant being regulated to what our Jewish communal gatekeepers considered the fringe of “normative” community. I was deeply saddened to hear in 2011, that he had been forced out of Baylor – but by then I knew enough to understand why. And though I had never met him, I felt compelled to join the voices who were rallying to his support.

This is what I wrote in my blog at the time:

I first read Professor Marc Ellis’ book “Toward a Jewish Theology of Liberation” as a rabbinical student back in the mid-1980s – and suffice to say it fairly rocked my world at the time. Here was a Jewish thinker thoughtfully and compellingly advocating a new kind of post-Holocaust theology: one that didn’t view Jewish suffering as “unique” and “untouchable” but as an experience that should sensitize us to the suffering and persecution of all peoples everywhere.

And yet further: Ellis had the courage to take these ideas to the place that few in the Jewish world were willing to go. If we truly believe in the God of liberation, if our sacred tradition truly demands of us that we stand with the oppressed, then the Jewish people cannot only focus on our own legacy of suffering – we must also come to grips with our own penchant for oppression, particularly when it comes to the actions of the state of Israel. And yes, if we truly believe in the God of liberation this also means that we must ultimately be prepared to stand with the Palestinians in their struggle for liberation.

When I first read Ellis’ words, I didn’t know quite what to make of them. They flew so directly in the face of such post-Holocaust theologians as Elie Wiesel, Rabbi Irving Greenberg and Emil Fackenheim – all of whom viewed the Jewish empowerment embodied by the state of Israel in quasi-redemptive terms. And they were certainly at odds with the views of those who tended the gates of the American Jewish community, for whom this sort of critique of Israel was strictly forbidden.

Over the years, however, I’ve found Ellis’ ideas to be increasingly prescient, relevant – and I daresay even liberating. As a rabbi, I’ve come to deeply appreciate his brave willingness to not only ask the hard questions, but to unflinchingly pose the answers as well.

Three years after I wrote those words, I ran into some professional difficulties of my own. Up until that point, the congregation I had served for the past 17 years had found a way to countenance my increasing Palestine solidarity activism. But gradually, perhaps inevitably, discord grew in my congregation. In early 2014, I learned that a small group of members had organized and wrote an open letter to our board demanding that they rein me in. When I spoke out publicly during Israel’s 2014 assault on Gaza, their calls grew even stronger. When I participated in a public disruption at a Chicago Jewish Federation fundraiser for the war effort, the tensions grew yet worse still. Then I was ejected from the Board of Rabbis of Greater Chicago. In the fall of 2014, I made the anguishing decision to resign from my congregation.

It was an enormously painful and traumatic time in my life and for the most part I’ve avoided speaking about it publicly. I’ll just say for now that when all this went down, I didn’t know if I could be a rabbi any more. I didn’t know how I would continue to be Jewish any more.

Less a week later, I learned that Marc had written about my resignation in his column at Mondoweiss. I was astonished – I had no idea he’d even heard of me. But here he was voicing his public approval and support of my actions, and in such classically Marc Ellis fashion:

The Jewish Reconstructionist Synagogue in Evanston, Illinois is looking for a new rabbi. Rabbi Brant Rosen is moving on. No one who is really going to look Israel in the eye need apply…

The whole thing is sad beyond words – who we have become. Rosen is one of the few rabbis in America with an ethical spine. He’s an outspoken advocate for Palestinian rights and co-chair of the Jewish Voice for Peace Rabbinical Council. I’m not sure what more needs to be said to analyze the situation.

Jewish congregational life, no matter how divided, can’t support Jewish leadership that has the prophetic at its core…Maybe the war in Gaza was the final straw. Rabbi Rosen and his congregation came face to face with the end-times of Jewish history. Rosen stood fast. It seems that Rabbi Rosen’s synagogue leadership blinked. What happened behind the scenes will probably remain secret – except for the voluminous leaks that are part of the vibrancy of congregational life.

Voluntary or forced and probably a combination of the two, Rabbi Rosen has his ticket to ride.

The Jewish rails?

Exile it is Rabbi Rosen! Welcome to the New Diaspora!

Shortly after his post appeared, I spoke with Marc on the phone. At first he was apologetic, hoping that he did not make things even more complicated for me. I reassured him that at that point, nothing could really make things more complicated than they already were. During our long conversation he told me something that he’s told me several times since. He said I needed to grasp how my participation in the Federation disruption was, in fact, contrary to everything I was trained to be in rabbinical school. What rational reason could possibly explain why I did this? For a congregational rabbi to disrupt a room filled with hundreds of Jewish leaders and community members? Why did I do it? How could I possibly explain it rationally?

In a subsequent article, Marc wrote further:

Out of the blue the prophets arise, are shot down, then reappear. It hasn’t changed much in thousands of years. The prophetic is too deeply ingrained in Jewish life to pass quietly into our newly embraced colonial night.

Apparently, synagogues are not for prophets. Those who practice the prophetic and attend synagogue, should take note. Your expulsion is inevitable.

The prophetic was happening, in Evanston of all places. Now Rabbi Rosen is packing his bags. With his conscience intact.

While I realize that Marc was offering out his hand in friendship and support at that moment, I think his gesture went even deeper than that. Though I sense his ideas about the prophetic have been informed by his own personal experience, I don’t think they come from a place of self-aggrandizement. After all, personal and professional banishment is not a pleasant experience. It is anguishing. It is traumatic. It is emotionally wounding. Marc wasn’t simply joking when he wrote, “Welcome to the New Diaspora, Rabbi Rosen!” He was letting me know that he had been there too and that yes, this “New Diaspora” as he called it, could be a brutal place. But he was also reassuring me that despite the trauma I was experiencing, even though I had lost everything I had thought to be Jewish up until then, I needed to understand that I had indeed acted in authentically Jewish fashion.

To hear this from someone I considered to be an intellectual and spiritual mentor meant the world to me. Ultimately it helped me to understand my actions as something other than merely ill-advised career suicide.

Now that I’m a few years removed from that time, I’m delighted to say that I’ve been able to carve out a fairly comfortable corner in the New Diaspora. It is, in fact, a steadily growing corner – and much of this is due to the path Marc has painfully charted. We’re witnessing the growth of what Marc would call a Jewish community of conscience. It is primarily an activist community, expressed through organizations such as Jewish Voice for Peace. I daresay those who have found a home in this community owe a significant debt to Marc whether or not they stop to realize it. I’ve tried to do my part in ensuring they know that Marc Ellis is, in no small way, their spiritual forbearer.

At the same time, I am acutely aware that he is not – and does not consider himself – an activist. As one who understands the Jewish prophetic to its core, he does not flinch from critique even of activist Jews of conscience like myself. As you all know, he perfectly willing to call out any behavior or analysis that he feels lacks depth – and the growing Jewish movement of solidarity with Palestinians is not immune from this critique. Like the prophets of old, he has no trouble serving as an equal-opportunity annoyance. Or maybe he just can’t help himself. Either way, Marc’s keen eye keeps us all honest.

In the spring of 2015, in an attempt to create a spiritual home for Jews of Conscience, I founded a congregation, Tzedek Chicago. True to form, Marc greeted this news with a characteristic blend of joy, skepticism, amusement and hope.

Here’s what he wrote in Mondoweiss:

We have arrived at the end of Jewish history and now another, prophetic, opportunity presents itself. Life is strange that way. Why worry about a failed future when the abyss we Jews inhabit is so obvious?

So fare forward, Tzedek Chicago. The deep and treacherous Jewish waters you ply are uncharted.

Or are they? Another way of being Jewish in the world is a return to our prophetic origins.

Yes, I hesitate. Yes, I join. As a witness at the end. With hope that there is more.

In more ways that he knows, he has helped to inspire our new “congregation of the abyss.” So yes, Marc Ellis has become a member of a synagogue. Yes, I am now Marc Ellis’ rabbi.

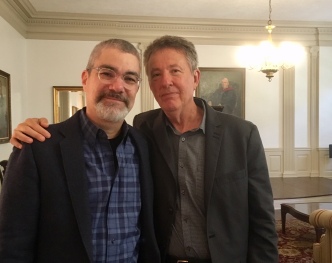

Last year, Tzedek Chicago brought out Marc to be our congregation’s scholar in residence, on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of “Toward a Theology of Jewish Liberation.” For Marc, it was the opportunity to teach in a Jewish space for the first time in many years. For me, it marked the turning of a significant cycle in my life that began that day in 1988, when I took a book off the shelf of my rabbinical school library, with no way of knowing that it would become a kind of spiritual bellwether for my own journey.

Today we celebrate another important milestone – a long overdue gathering of Marc’s friends, colleagues, students and children. To quote Marc, “the deep and treacherous Jewish waters we ply are uncharted.” But we are charting them together. If we have indeed arrived at the end of Jewish history, I have faith that together we will discover how to begin it anew.

I will end with a quote from Marc’s book – it’s a passage that resonates with deeper meaning each time I return to it:

Prophetic Jewish theology, or a Jewish theology of liberation, seeks to bring to light the hidden and sometimes censored movements of Jewish life. It seeks to express the dissent of those afraid or unable to speak. Ultimately, a Jewish theology of liberation seeks, in concert with others, to weave disparate hopes and aspirations into the very heart of Jewish life.

I can think of no better mission statement for life in the New Diaspora.