Introduction

In the spring of 2015, I helped to establish a Jewish congregation, Tzedek Chicago, motivated in part by a desire to create a religious space for those in the Jewish community who did not consider themselves to be Zionists. The founders of the congregation articulated this intention openly, in a core value we called “Judaism Beyond Nationalism:”

While we appreciate the important role of the land of Israel in Jewish tradition, liturgy and identity, we do not celebrate the fusing of Judaism with political nationalism. We are non-Zionist, openly acknowledging that the creation of an ethnic Jewish nation state in historic Palestine resulted in an injustice against its Indigenous people – an injustice that continues to this day.

In the contemporary Jewish community, of course, identification with the Zionist narrative has become the sine qua non of Jewish identity. While it is beyond the scope of this essay to analyze the process by which Zionism – a 19th century European nationalist ideology that represented a radical departure from traditional Judaism – became normalized in the American Jewish community, it is fair to say that since the founding of the state of Israel, Zionism has become thoroughly enmeshed in the culture of American Jewish life.

There are signs, however, that the linkage between Zionism and Judaism has begun to loosen in the Jewish community – particularly among younger Jews. According to a widely read 2013 Pew Research Center Study, 27% of American Jews aged 18 to 29 do not feel “very attached” to Israel and another 11% feel “not at all attached.” In a 2017 study commissioned by the Jewish Community Federation of San Francisco reported that among Bay Area Jews, 22 % of the respondents reported that a Jewish state’s existence is “not important” or were “not sure.”

Beyond individual attitudes, the nascent beginnings of a “Judaism beyond Zionism” are organically developing outside the bounds of the Jewish communal establishment. As Atalia Omer has written,” we are witnessing the emergence of a “grassroots movement that seeks…to transformatively reimagine American Jewish identity outside the Zionist paradigm.” 1 Though still a distinct minority, the growth of American Jewish organizations such as Jewish Voice for Peace, #IfNotNow, the Center for Jewish Nonviolence and Open Hillel attest to burgeoning desire for a Judaism that unabashedly challenges Jewish communal support for Israel’s occupation – and in some cases, the very concept of Jewish statehood itself. 2

Another important indication of this shift occurred when Jewish Voice for Peace – an organization that promotes Jewish solidarity with Palestinians and “unequivocally opposes Zionism” – broadened its mission to include the goal of “Jewish Communal Transformation.” In 2011, JVP created its Rabbinical Council to provide “a prophetic Jewish voice inside the Palestine solidarity movement (and) create meaningful ritual, tradition and culture accessible to our growing membership.” JVP subsequently established its own Havurah Network, which it described as “an emergent network that gathers, supports and resources anti-zionist, non-zionist and diasporist Jews and Jewish spiritual communities across the country yearning for a vibrant Jewish life beyond nationalism that condemns and challenges white supremacy within and outside Jewish communities.”

1 Atalia Omer, Days of Awe: Reimagining Judaism in Solidarity with Palestinians, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019, p. 68.

2 Another important sea change occurred in July 2020, when prominent Jewish journalist Peter Beinart, a long-time Liberal Zionist, wrote the New York Times op-ed, “I No Longer Believe in a Jewish State.”

Jewish Diasporism

This newly emergent Judaism beyond Zionism is increasingly being described in positive terms as Jewish diasporism. While this term may seem redundant, we cannot underestimate the extent to which the importance of the Jewish diaspora 3 has been undermined in the era of Zionism. In an age when the idea of Jewish statehood has become thoroughly normalized, however, it is well worth remembering that Rabbinic Judaism originally emerged as a spiritual response to the experience of Jewish dispersion.

Before the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 ACE, Judaism was a land-centered, Temple-based sacrificial system that was splintering into several competing sects. When the Temple was destroyed and the center of Jewish life shifted from land to diaspora, the rabbis adapted to this new reality accordingly, developing a religious system that could be observed anywhere in the world.

In truth, thriving Jewish diaspora communities existed well before the destruction of the Temple. When Cyrus the Great allowed the exiled Jewish community of Babylon to return to the land in 538 BCE, scores remained in Persia where they enjoyed relative economic stability, “unswayed by the promises of a distant homeland they had never seen.” 4 There were also significant diaspora Jewish communities throughout the Hellenistic world. Between the third century BCE and the end of the first century CE, Alexandria, Egypt became one of the most populous Jewish communities in the world, numbering at least several hundred thousand.

Judaism’s foundational Jewish text – the Talmud – was itself composed and compiled in Babylonia. In a similar way, the myriad of lands in which Jews have lived have provided fertile soil for Jewish spiritual creativity throughout the centuries. Indeed, the most important Jewish religious figures clearly reflect their specific cultural time and place: the great 10th century Jewish philosopher Saadia Gaon, the founder of Judeo-Arabic literature, integrated Jewish theology with the Hellenistic Greek philosophy of his day; Maimonides’ classic philosophical treatises were deeply influenced by the neo-Aristotelian philosophy of medieval Spain; Franz Rosenzweig’s work clearly reflects the ideas of modern German liberalism.

This is not to say that the land of Israel ceased to become important in Jewish tradition. The symbolism of the major Jewish holidays is deeply rooted in the seasonal/agricultural rhythms of the land. A great deal of rabbinic debate in classical Jewish writings focused on how Biblical laws specifically pertaining to the land might be observed in a diasporic setting. There was also extensive theological speculation as to whether or not the land itself was inherently holy or whether it’s holiness derived from the commandments that were fulfilled there. 5

The rabbis also debated whether or not it was a mitzvah (religious obligation) for individual Jews to emigrate to the land. 6 At the same time, however, rabbinic authorities were virtually united in their opposition to the political reestablishment of a Jewish commonwealth. While a yearning for the restoration of Zion is undeniably central to rabbinic Judaism, this ideal was expressed within a decidedly messianic context. Jewish tradition is replete with strong warnings against the creation of a sovereign Jewish state via human agency. 7

When political Zionism arose in the 19th century, it consciously sought to overturn the diasporic focus of Jewish life. A central Zionist dictum known as shlilat hagalut (“negation of the diaspora”) viewed the diaspora as an inherently inhospitable place for Jews; only through the establishment of a Jewish state in their “ancient homeland” would the Jewish people normalize and safeguard their existence among the nations.

Many classical Zionist figures were so vehement in their rejection of the diaspora that their descriptions of European Jewry reflected a palpable sense of internalized antisemitism. Zionist writer/journalist Micha Josef Berdichevski opined for instance, that the Jews of the pale were “not a people, not a nation, not human.” 8 Hebrew poet/author Joseph Chaim Brenner called diaspora Jews “Gypsies and filthy dogs” 9 and the Labor Zionist icon A.D. Gordon wrote that diaspora Jewish life was the “parasitism of a fundamentally useless people.” 10 The views of Revisionist Zionist founder Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky, who was clearly influenced by European fascist ideology, infamously referred to religious diaspora Jews as “ugly, sickly Yids” and Zionist settlers as “Hebrews.” 11

Now six decades after the founding of the state of Israel, however, it might be claimed that the Jews who live there are experiencing a new form of exile. 12 On the eve of its establishment, the celebrated Jewish German political theorist Hannah Arendt presciently warned that the new Jewish state would be “secluded inside ever-threatened borders, absorbed with physical self-defense to a degree that would submerge all other interests and activities.” 13 Today, Israel is one of the most militarized nations in the world, a virtual garrison state with a traumatized national culture. More tragically, the movement that ostensibly sought to end Jewish exile ended up exiling another people in the process. The state of Israel was created through the expulsion of the Palestinians, who today live under military occupation, as second-class citizens in their own land, or else in a diaspora of their own – as refugees or citizens of other countries – and are forbidden to return to their homes.

The Jewish population of the world is currently split almost in half between Israel and the diaspora. Where does this leave those in the diaspora who choose not to center our Judaism on the state of Israel; who refuse to celebrate a Judaism that glorifies ethnic Jewish nation-statism? Is there a place for Jews who want to celebrate the diaspora as dynamic and fertile ground for a new kind of Judaism? One that embraces Jewish existence among diverse nations as a multi-ethnic, multi-racial peoplehood? One that advocates for the universal redemption of all peoples?

Over the past two decades, prominent Jewish scholars have been reclaiming and reframing the concept of Jewish diaspora in compelling ways. Melanie Kaye Kantrowitz, for instance, has advocated a conscious celebration of the diaspora as part of a larger project of Jewish empowerment:

Celebrating dispersion, Diasporism challenges the Edenic premise: once we were gathered in our own land, now we are in exile. What if we conceive of diaspora as the center: an oxymoron, putting the margin at the center of the circle that includes but does not privilege Israelis?… Jews worldwide number only about 13.3 million, a tiny minority except in Israel. Diasporism means embracing this minority status, leaving us with some tough questions: Does minority inevitably mean feeble? Can we embrace diaspora without accepting oppression? Do we choose to be marginal? Do we choose to transform the meaning of center and margins? Is this possible? 14

Daniel Boyarin has argued that the Babylonian Talmud itself is a “diasporist manifesto,” imagining its own community and sense of portable homeland:

The Talmud in its textual practices produces Babylonia as a homeland, and since this Babylonia is produced by a text that can move, that homeland becomes portable and reproduces itself over and over. The Talmud, I would submit, is not only the only classical work of the rabbinic period produced outside the Land of Israel; it is a diasporist manifesto, Diasporist Manifesto Number 1. 15

More recently, Susannah Heschel has suggested the concept of diaspora as a prophetic alternative to the traditional Jewish “embrace of exile:”

As prophetic, the diasporic Jew is never entirely at home, never content or complacent in a world of injustice. Diaspora transforms exile into Jewish creativity, as has happened for over two millennia. The prophet is a diasporic exemplar, leaving home and journeying to the urban seat of the political, military, and economic power to demand an end to corruption, exploitation, cruelty, and indifference. The prophetic position cannot exist by trying to end exile with statehood or by embracing exile as the essential mentality of Jewishness. To abandon diaspora in favor of exile is to walk away from the prophetic; to reject exile while embracing diaspora is to retain the prophetic passion for justice.

In short, we are currently witnessing the emergence of a new Jewish diasporism: one that neither stigmatizes existence outside the land nor romanticizes the experience of exile, but rather seeks to center the diaspora as the essential locus of Jewish life, creativity and purpose.

3 While I use the term “Jewish diaspora” here for the sake of clarity, it might be more accurate to refer to Jewish “diasporas,” as Jewish life throughout the world has existed in very different social, cultural and political milieus and throughout unique, distinct periods of world history.

4 H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1976, p. 168.

5 See Mishnah Kelim 1:6: “What is the nature of (the land’s) holiness? That from it are brought the omer, the firstfruits and the two loaves, which cannot be brought from any of the other lands.”

6 From Talmud Ketubot 110a: “Whoever lives outside of Israel may be regarded as one who worships idols.” From Ketubot 111a: “Whoever returns from Babylon to Israel transgresses a positive commandment of the Torah.”

7 The classic rabbinic prohibition against reestablishing the Jewish commonwealth before the coming of the Messiah is known as the “Three Oaths.” See Babylonian Talmud, Ketubot 110b, Shir Hashirim Rabbah, 8:11.

8 Walter Laqueur, A History of Zionism: From the French Revolution to the Establishment of the State of Israel, New York: Schocken, 1972, p. 61.

9 IBID.

10 IBID.

11 Alan Wolfe, At Home in Exile: Why Diaspora is Good for the Jews, Boston: Beacon Press, 2014, p. 17. For more on Zionist ideals of Jewish masculinity, see Daniel Boyarin, Unheroic Conduct: The Rise of Heterosexuality and the Invention of the Jewish Man, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

12 See Raz-Krakotzkin, Amnon, Exile Within Sovereignty: Critique of “The Negation of Exile” in Israeli Culture, from “The Scaffolding of Sovereignty: Global and Aesthetic Perspectives on the History of a Concept,”edited by Zvi Ben-Dor Benite, Sefanos Geroulanos, Nicole Jerr, pp. 393-420, New York, Columbia University Press, 2017.

13 Hannah Arendt, The Jewish Writings, New York: Schocken, 2007, p. 396.

14 Melanie Kaye Kantrowitz, The Colors of Jews: Racial Politics and Radical Diasporism, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2007, p. 200.

15 Daniel Boyarin, A Traveling Homeland: The Babylonian Talmud as Diaspora, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015, p. 32.

Jewish Diasporism at Tzedek Chicago

Since its founding, Tzedek Chicago has become a practical laboratory for the development of this new Jewish diasporism, particularly through the creation of rituals that explicitly celebrate the idea of “diaspora as homeland.”

During the holiday of Sukkot, for instance, instead of the traditional lulav and etrog – the four species native to the Biblical land of Israel – we use symbolic species indigenous to the prairie of the Midwestern United States. 16 We are exploring diasporist approaches to other Jewish holidays as well. On the festival of Tu B’shvat, which typically falls in late January/early March, I offered this teaching to the Tzedek Chicago community:

In the land of Israel, the “harbinger of Spring” festival of Tu B’shvat is marked at this time of year by the blossoming of the white almond blossoms through the central and northern parts of the land. However, those of us who live in the diaspora of the American Midwest, often celebrate Tu B’shvat surrounded by several inches of white snow and leafless trees. Is this any way to celebrate a harbinger of Spring?

I’ll suggest that it is. I actually find it very profound to contemplate the coming of Spring in the depths of a Chicago winter. It reminds me that even during this dark, cold season, there are unseen forces at work preparing our world for renewal and rebirth. Deep beneath the ground, the sap is beginning to rise in the roots of our trees – although this fructification process might not be as visually spectacular as the proliferation of white almond blossoms exploding across the countryside, I believe this invisible life-giving energy is eminently worth acknowledging – and celebrating.

It is true, of course, that the Biblical land of Israel was central to Judaism centuries before the ideology of political Zionism emerged. As such, some might well claim that the decentering of land-based symbolism represents a kind of “radical surgery” to Jewish tradition. If, as I noted above, Judaism originally spiritualized the concept of homeland, might we still retain its land-centric aspects for their symbolic, mythic power?

Such a question fails to confront the radical way Zionism has transformed Judaism itself and how deeply it has influenced Jewish attitudes toward the diaspora. Just as radically, diasporic Judaism seeks to re-right this imbalance by lifting up and centering the idea of Jewish home wherever we happen to live in the world. In Kaye Kantrowitz’s words, “Where Zionism says go home, Diasporism says we make home where we are.” 17 For those of us who affirm that the entire world is and has been our actual Jewish homeland, these new, reframed rituals seek to celebrate the Jewish people’s adaptability – and the unique nature of the homes we have created for ourselves throughout the diaspora.

Another, related issue is the concept of “Zion” itself, an idea that is undeniably, indelibly imprinted upon Jewish tradition and Jewish liturgy. How might a diasporic Judaism understand this concept, whose meaning has been thoroughly literalized by political Jewish nationalism?

As stated above, the idea of the Jewish return to Zion was traditionally understood in messianic terms. This belief is particularly embodied in the concept of kibbutz galuyot (“ingathering of exiles”), which emerged during the Babylonian exile as expressed in the Biblical books of Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel. 18 In Jewish liturgy, this concept is prominent in a number of prayers, including the Daily Amidah and Ahavah Rabbah (“Abounding Love”), a prayer that is traditionally read before the Shema during the morning service and ends with the line, “May we be glad, rejoicing in your saving power, and may you reunite our people from all corners of the earth, leading us proudly to our land.”

Zionism lifted kibbutz galuyot out of its messianic context and reframed it in explicitly nationalist terms. It is notably referenced in Israel’s Declaration of Independence as well as the Prayer for the Welfare of the State of Israel, both written in 1948 to explicitly celebrate the literal “exilic ingathering” of modern Jewry to the state of Israel. The Zionist interpretation of kibbutz galuyot has been internalized in American Jewish life as well. In many synagogues, for instance, it is even customary to sing the line “may you reunite our people” in the Ahavah Rabbah prayer to the melody from Hatikvah – the Israeli national anthem.

How might kibbutz galuyot be reimagined in a diasporist context? At Tzedek Chicago, our version of Ahavah Rabbah is rendered thus, “May it lead us toward your justice, toward liberation for all who dwell on earth; that all who are exiled and dispossessed may safely find their way home.” Our new reading replaces Jewish particularism and exceptionalism with a universalist, decolonial ethic. As such, it is neither messianic nor Zionist. In this post-modern diasporist reimagining, Zion is not unique to the Jewish people and does not exist in any particular place. So too, kibbutz galuyot does not refer to the Jewish exiled alone but to all who have been – or continue to be – dispossessed throughout the world.

16 In 2018, a small group of radical Jews published a zine that offered “reflections, tips, and resources about creating your own diasporic lulav,” explaining, “Our lulavs – both the ritual object and the ritual acts – are situated in diaspora, and explicitly reject the colonization of Palestine and the mandate to use the “four kinds” (“arbah minim”) of plants associated with the biblical Land of Israel.”

17 Kantrowitz, p. 199.

18 See Isaiah 11:12; 27:13; 56:8, 66:20, Jeremiah 16:15; 23:3, 8; 29:14; 31:8; 33:7 and Ezekiel 20:34, 41; 37:21. The term itself was coined in the Talmud (see Babylonian Talmud, Megillah 12a) and was later connected to the coming of the Messiah by Moses Maimondies (see Mishneh Torah, “Laws of Kings,” 11:1-2).

Jewish Anti-Militarism

In addition to re-centering diaspora, any attempt at promoting a Judaism Beyond Zionism must reckon seriously with the culture of militarism that thoroughly pervades the ideology of Zionism and Israeli society. As Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb has pointed out, “During the past sixty years, the assumption that a highly militarized Jewish state ensures Jewish security has become entrenched as an article of faith… To critique Israeli militarism is to critique Zionism in the minds of many contemporary Jews.” 19

Prior to the onset of Zionism, Jewish tradition promoted nonviolence and quietism over the glorification of war, 20 a doctrine generally traced to the aftermath of the Bar Kochba rebellion (132-135 CE). As Reuven Firestone has written, in the wake of this catastrophic event, “Jewish wisdom would teach that it is not physical acts of war that would protect Israel from its enemies, but rather spiritual concentration in righteousness and prayer.” 21

The rabbis were also painfully aware that the Hasmonean revolt centuries earlier had ended disastrously for the Jewish people. This uprising, chronicled in the Books of the Maccabees and commemorated by the festival of Hanukkah, was waged by the Maccabees, a priestly family who led a rebellion against the religious persecution of the Seleucid empire. Their victory resulted in the establishment of the Hasmonean Kingdom – the second Jewish commonwealth – in Palestine in 164 BCE.

The militarism of the Hasmoneans however, would eventually prove to be its downfall. Following the Maccabean victory, their brief period of independence was wracked by internecine violence, anti-rabbinic persecution and ill-advised wars of conquest against surrounding nations. In 63 BCE, the Hasmonean Kingdom was conquered by the Romans (with whom they had previously been allied). In the end, the last period of Jewish political sovereignty in the land lasted less than one hundred years. 22

The rabbis of the Talmud were loath to glorify the Books of the Maccabees – secular stories of a violent civil war that were never actually canonized as part of the Hebrew Bible. In fact, the festival of Hanukkah is scarcely mentioned in the Talmud beyond a brief debate about how to light the Hanukkah menorah and a legend about a miraculous vial of oil that burned for eight days. 23 Notably, the rabbis chose the words of Zechariah 4:6, Not by might and not by power, but by my spirit, says the Lord of Hosts to be recited as the prophetic portion for the festival.

Hanukkah remained a relatively minor Jewish festival until it was revived by early Zionists and the founders of the state of Israel, who fancied themselves as modern-day Maccabees engaged in their own military struggle for political independence. At the end of his book, The Jewish State, Zionist movement founder Theodor Herzl famously wrote, “The Maccabees will rise again!” 24 Even today, the celebration of the Maccabees as Jewish military heroes is deeply ingrained in Israeli culture.

This Zionist sacralizing of militarism and conquest represented a radical overturning of these central tenets of traditional Judaism. The term kibush ha’aretz (“conquest of the land”) was one of the terms used by Zionist settlers to describe their colonization of Palestine. 25 As noted above, many Zionist ideologues promoted the ideal of the muscular, heroic “New Jew” in contrast with Diaspora Jewry. Zionists were also instrumental in helping to form the Jewish Legions that fought against the Ottomans in Palestine in World War 1. During the British Mandate, Zionists created armed militias such as the Haganah (which later became the Israeli Defense Force after the founding of the state) as well as the more militant Irgun and Lehi.

In 1948-49, during what Jewish Israelis refer to as their War of Independence and Palestinians call the Nakba (the “catastrophe”), these armed forces engaged in the widespread ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from villages and cities throughout Palestine. Notably, these military operations often used names associated with Biblical history and Jewish religious tradition. For instance, a joint force of the Haganah and Irgun dispossessed 61,000 Palestinians from Haifa on eve of Passover 1948, in a campaign known as “Operation Biur Chametz,” (“Operation Cleaning Out the Leaven”) – a reference to the commandment to remove leaven from Jewish homes before the onset of the festival. 26 Another campaign, waged in the southern Negev desert and the coastal plain was given the name “Operation Ten Plagues.” 27

The Zionist movement and the fledgling state of Israel notably looked to the Biblical conquest tradition – and in particular, the Book of Joshua – as a model for its own conquest of historic Palestine. Though largely secular, Israel’s founders utilized the Bible as a canvas for promoting a national myth of a glorious military past. As scholar Nur Masalha has pointed out, “The Book of Joshua provided Ben-Gurion, Jabotinsky and muscular Zionism with the militaristic tradition of the Bible: of military conquest of the land and subjugation of the Canaanites and other ancient people that populated the ‘promised land.” 28 Ben Gurion himself viewed the book of Joshua as the most important book of the Bible; in 1958 he convened a study group at his home where Israeli generals, politicians, and academics discussed the book of Joshua against the founding of the modern state of Israel. 29

19 Lynn Gottlieb, Trail Guide to the Torah of Nonviolence, France: Earth of Hope Publishing, 2013, p. 19.

20 Reuven Firestone, Holy War in Judaism: The Fall and Rise of a Controversial Idea, New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

21 IBID, p. 62.

22 For more on the history of the Hasmonean Kingdom, see Kenneth Atkinson, A History of the Hasmonean State: Josephus and Beyond, London: T&T Clark, 2016.

23 See Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 21b.

24 Arthur Hertzberg, ed., The Zionist Idea, Canada: Atheneum, 1959, p. 225.

25 Firestone, pp. 181-182.

26 Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 186-211.

27 IBID, p. 462.

28 Nur Masalha, The Bible and Zionism: Invented Traditions, Archaeology and Post-Colonialism in Israel-Palestine, London: Zed Books, 2007, p. 24.

29 See Rachel Haverlock, The Joshua Generation: Israeli Occupation and the Bible, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020.

Jewish Anti-Militarism at Tzedek Chicago

At Tzedek Chicago, our core values clearly and unabashedly condemn the glorification of war and violence. This is both a return to the traditional rabbinic approach as well as step beyond it. Our vision of Jewish nonviolence does not emerge from quietism but rather from the value of solidarity: the conviction that security for Jews is irrevocably bound up with security for all.

As we state in our core values:

In our education, celebration and communal observances, we honor those aspects of our tradition that promote peace and reject the pursuit of war as a solution to our conflicts. We openly disavow those aspects of our religion – and all religions – that promote violence, intolerance and xenophobia.

Our activism is based upon a vision of shared security for the world; we support the practices of nonviolence, civil resistance, diplomacy and human engagement. Through our advocacy, we take a stand against militarism and colonialism, particularly when it is waged in our name as Jews and Americans.

Liturgically, we express this value in a variety of ways. For instance, in our poetic rendering of the prophetic portion for Hanukkah (Zechariah 2:14-4:7), the rededication of the Temple by the Maccabees is reframed as a dedication to ideals of nonviolence and justice for all people:

Let loose your joy for

your prayers have

already been answered;

even in your exile

the one you seek has been

dwelling in your midst

all along.

Quiet your raging soul

and you will come to learn:

every nation is my nation

all peoples my chosen

anywhere you choose to live

will be your Holy Land,

your Zion, your Jerusalem.

Open your eyes and

look across the valley

look at this ruined land

seized and possessed

throughout the ages.

Look upon your

so-called city of peace

a place that knows

only debasement

and desecration

at your hand.

Turn your gaze to the heavens

and there you will find

the Jerusalem that you seek:

a city that can never be conquered,

only dreamed of, yearned for, strived for;

a Temple on high that can never be destroyed.

No more need for priestly vestments

or plots to overrun that godforsaken mount –

just walk in my ways

and you will find your way there:

a sacred pilgrimage to the Temple

in any land you call home.

Enter the gates to

this holiest of holy places,

lift up its fallen walls,

relight the branches of the lamp

so that my house will truly

become a sanctuary

for all people.

Yes, this is how you will

restore the Temple:

not by might, not by power

but by the spirit

you share with every

living, breathing soul.

These values are also reflected in our Prayer for Reparation and Restoration. which we read in lieu of the congregational Prayer for Peace or Prayer for the Welfare of the Government. (Compare our prayer below for instance, with the Reform Movement’s “Prayer for Peace and Strength:”)

To the One who demands justice:

inspire us to become rodfei tzedek,

pursuers of justice

in our lives and in our communities.

Give us the strength to resist power

wielded with fear and dread;

fill us with the vision and purpose

to build a power yet greater,

a power rooted in solidarity,

liberation and love.

Grant us the courage to dismantle

systems of oppression –

and when they are no more,

let us dedicate our wealth and resources

toward the well-being of all.

May we abolish all forms of state violence

that we might make way for a world

free of racism and militarization,

a world where no one profits

off the misery of others,

a world where the bills owed those who have been

colonized, enslaved and dispossessed

are finally paid in full.

Inspire us with the knowledge

that real justice is indeed at hand,

that we may realize

the world we know is possible,

right here, right now,

in our own day.

May our thoughts and our hopes,

our words and our deeds

guide us toward a future of reparation,

of restoration, of justice,

al kol yoshvei teivel

for all who dwell on earth,

amen.

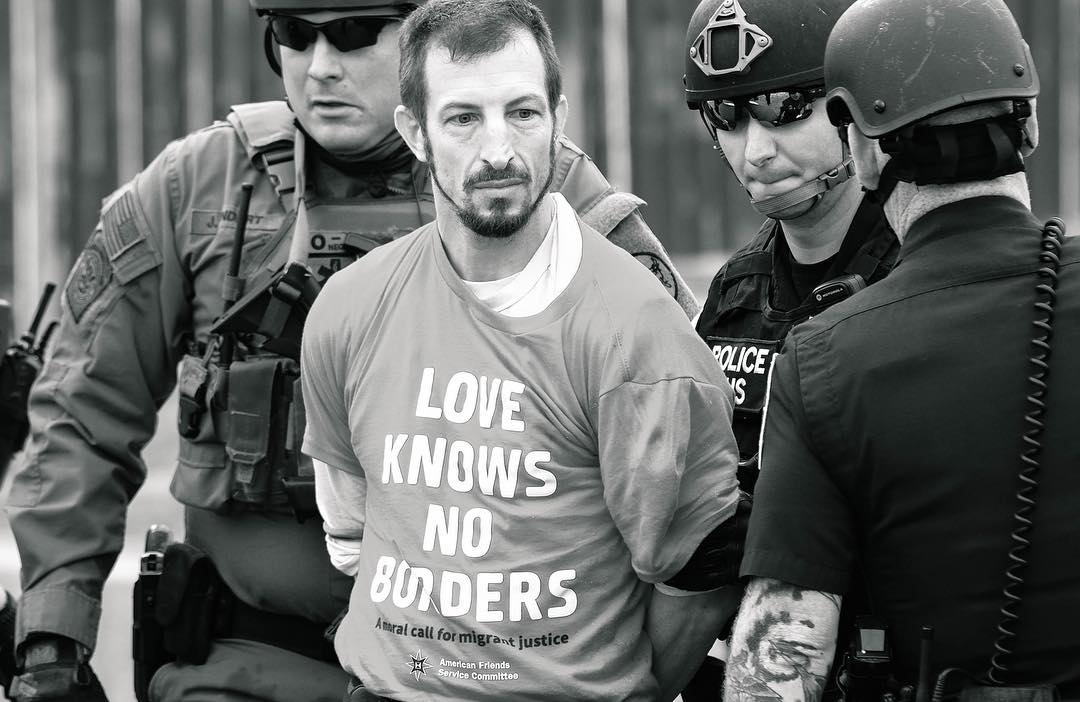

As a response to the issue of domestic militarization, the prayer below was delivered at a Tisha B’Av vigil, co-sponsored by Tzedek Chicago, at an immigrant detention center in Kankakee, IL. The text is an adaptation from the Biblical book of Lamentations, traditionally read on the festival of Tisha B’Av:

We are beyond humiliation

beyond shame

we incarcerate children without pity

we deport parents without a thought

and build systems that destroy families indiscriminately

now we truly know what it means to be dishonored

our so-called glorious past is now seen

for the sham that it was

the way of life we celebrate is but a privilege

for the few and the powerful

we can’t see that our own might

will be our downfall.

We venerate leaders

who should be tried for their crimes

we never dared imagine a power

greater than our own

like so many before us

we conquered the land then drew borders

as a testament to our fear and dread

now we build higher walls

to keep out those who seek shelter

we built massive checkpoints

we lined up human beings

like cattle in cages

now children cry out for parents

who will never answer their calls

their voices echo endlessly

through the camps but there

is no one left to hear.

We ask one another with bewilderment

have we ever seen such cruel violations

yet in truth we ourselves have inflicted

such cruelties on children here

and around the world

we sentence minors to life in prison without parole

we remain silent as a cruel occupation

abducts and imprisons children in military prisons

convicts them in military courts

and yet we dare to act surprised when

we hear news of children thrown into cages

at our southern border.

Our silence betrays us

these walls will soon encircle us all

soon there will be no one left

only a single mass of mourners

whispering broken hymns of lament

grieving what was lost

and what might have been

one day we will know the sorrow

of the dispossessed.

We who never heard the cries of migrants

and their children will know what it means

to be uprooted detained and discarded

those who we scorned and abandoned

will bitterly welcome us to the world

of the dispossessed

the enemies we created

through our own fearful actions

will surely come back for us all.

Let us hope and pray

there is still time

let the cries of our children

pour into our hearts like water

the cries of any who have been forced

from their homes pursued

taken locked away sent away

anyone whose very lives are forbidden

forgotten forsaken

let their cries compel us

to take down oppressive systems

built by the powerful to maintain

the power of the powerful.

Let their cries remind us

that there is a power yet greater

that comes from a place that knows no borders

no deportations no barrier walls no prisons

no guards no soldiers no ICE no police

a place where we no longer need to struggle because

justice gushes forth like a mighty stream flowing freely.

From the sovereign beyond all sovereigns

we beseech you chadeish yameniu

renew our days

that we may build the world

that somehow still might be

kein yehi ratzon – may it be your will

and may it be ours.

Jewish Solidarity with Palestinians

At Tzedek Chicago, we understand solidarity with Palestinians not merely as a political position, but a sacred imperative. As we state in one of our core values, that “the creation of an ethnic Jewish nation state in historic Palestine resulted in an injustice against its indigenous people.” Accordingly, we reject the ways that the establishment of the state of Israel has become sacralized as redemptive in most American synagogues.30 Needless to say, for those Jews who consider the Nakba to be an historic – and ongoing – injustice, the birth of the Jewish state has a decidedly different religious meaning.

We express our sacred solidarity with Palestinians in a variety of ways. One Passover, for instance, we invited Omar Barghouti, co-founder of the Palestinian movement for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions, to our congregation to speak about BDS as a liberation movement. In our advertising, we described the program thus: “Taking our cue from the season of Passover we will engage in a deep exploration of this important call for Palestinian liberation, and explore its profound challenge to all people of conscience.”

Tzedek Chicago also expresses Jewish solidarity with Palestinians through the use of sacred ritual. For instance, while most American synagogues celebrate Yom Ha’atzmaut (Israel Independence Day) as part of the Jewish religious calendar, we observe this occasion through our recognition of Nakba Day – the day Palestinians mark as the day of their catastrophic dispossession. In our “Jewish Prayer for Nakba Day” we use traditional Jewish liturgical/theological imagery to reflect our observance of this day as an occasion for mourning, remembrance and repentance:

Le’el she’chafetz teshuvah,

to the One who desires return:

Receive with the fulness of your mercy

the hopes and prayers of those

who were uprooted, dispossessed

and expelled from their homes

during the devastation of the Nakba.

Sanctify for tov u’veracha,

for goodness and blessing,

the memory of those who were killed

in Lydda, in Haifa, in Beisan, in Deir Yassin

and so many other villages and cities

throughout Palestine.

Grant chesed ve’rachamim,

kindness and compassion,

upon the memory of the expelled

who died from hunger,

thirst and exhaustion

along the way.

Shelter beneath kanfei ha’shechinah,

the soft wings of your divine presence,

those who still live under military occupation,

who dwell in refugee camps,

those dispersed throughout the world

still dreaming of return.

Gather them mei’arbah kanfot ha’aretz

from the four corners of the earth

that their right to return to their homes

be honored at long last.

Let all who dwell in the land

live in dignity, equity and hope

so that they may bequeath to their children

a future of justice and peace.

Ve’nomar

and let us say,

Amen.

Le’el she’chafetz teshuvah,

to the One who desires repentance:

Inspire us to make a full accounting

of the wrongdoing that was

committed in our name.

Help us to face the terrible truth of the Nakba

and its ongoing injustice

that we may finally confess our offenses;

that we may finally move toward a future

of reparation and reconciliation.

Le’el malei rachamim,

to the One filled with compassion:

show us how to understand the pain

that compelled our people to inflict

such suffering upon another –

dispossessing families from their homes

in the vain hope of safety and security

for our own.

Osei hashalom,

Maker of peace,

guide us all toward a place

of healing and wholeness

that the land may be filled

with the sounds of joy and gladness

from the river to the sea

speedily in our day.

Ve’nomar

and let us say,

Amen.

In another example of communal Palestinian solidarity, we dedicated a portion of our 2018 Yom Kippur Service to the Palestinians who were then being killed weekly by the Israeli military in Gaza’s Great Return March. In the introduction to this ritual, we stated:

It is traditional at the end of the Yom Kippur morning service to read a Martyrology that describes the executions of ten leading rabbis, including Rabbi Akiba, Rabbi Shimon ben Gamliel and Rabbi Yishmael, who were brutally executed by the Roman Empire. This liturgy is included to honor those who have paid the ultimate price for the cause of “Kiddush Hashem” – the sanctification of God’s name.

At Tzedek Chicago, we devote the Yom Kippur Martyrology to honor specific individuals throughout the world who have given their lives for the cause of liberation. As we do, we ask ourselves honestly: what have we done to prove ourselves worthy of their profound sacrifices? And what kinds of sacrifices will we be willing to make in the coming year to ensure they did not die in vain?

This year, we will dedicate our Martyrology service to the Palestinians in Gaza who have been killed by the Israeli military during the Great Return March. This nonviolent demonstration began last spring with a simple question: “What would happen if thousands of Gazans, most of them refugees, attempted to peacefully cross the fence that separated them from their ancestral lands?”

Since the first day of the march last spring, demonstrators have consistently been met by live fire from the Israeli military. To date, 170 Palestinians have been killed and tens of thousands wounded and maimed, most of them unarmed demonstrators, including children, medics and bystanders.

30 This sacralization is reflected in a myriad of ways, whether it be through the placement of the Israeli flag next to the ark containing the sacred scrolls of the Torah, the regular recitation of the “Prayer for the State of Israel” (which refers to its establishment as “the first flowering of our redemption,”) or the celebration of Yom Ha’atzmaut (Israeli Independence Day) alongside traditional Jewish festivals.

Decolonial Judaism

As we have explored the meaning of Judaism beyond Zionism, we have quickly come to realize that many of these issues are rooted in more foundational concerns. For instance, we cannot interrogate the meaning of the Jewish diaspora without also understanding the diasporas of other transnational and/or dispossessed peoples. As we grapple with issues of militarism we must invariably confront the connections between state violence and structural racism. Solidarity with Palestinians cannot be viewed in isolation from the larger legacy of settler colonialism and the dispossession of Indigenous Peoples in the US and around the world.

These connections have, in turn, given rise to critical questions, such as:

• In North America, white Jews are participants in the ongoing colonization of stolen land. How can we celebrate diaspora in a way that respects the land upon which we live and the Indigenous Peoples for whom it remains sacred?

• In the United States, 12 to 15% of the American Jewish community are Jews of color, many of whom have their own history of colonization and enslavement. How will white Jews center their experience and stand down the culture of White supremacy in the American Jewish community?

• If we view atonement as a sacred imperative, how can we, as a Jewish congregational community advocate and participate in a process of reparations and rematriation for the members of Indigenous Nations and descendants of enslaved people?

As a response to questions such as these, Tzedek Chicago has convened an internal task force “to explore how Tzedek as a community can best participate and support reparative justice efforts, especially regarding the harms of slavery and colonization.” We are also exploring ways to address these questions through Jewish ritual. In 2019, for instance, we celebrated a Sukkot festival celebration jointly sponsored with Chi-Nations Youth Council – a Chicago-based group that organizes on behalf of Native Youth in the region. Our celebration included the prayer, “Earth Shema,” written for Tzedek Chicago by poet/liturgist Aurora Levins Morales:

There is no earth but this earth and we are its children. The earth is our home, and there is only one. The ground beneath our feet was millions of years in the making. Each leaf, each blade, each wing, each petal, each hair on the flank of a red fox, each scale on the sturgeon, each mallard feather, each pine needle and fragment of sassafras bark took millions of years to become, and we ourselves are millions of years in the making.

The earth offers itself and all its gifts freely, offers rain and sunlight, and the shimmer of moon on its lakes, offers corn and squash, apples and honey, salmon and lamb, and clear, cold water and all it asks in return is that we love it, respect its ways, cherish it.

We shall love the earth and all that lives with all our hearts, with all our souls, with all our intelligence, with all our might.

Wherever we walk, wherever we sleep, wherever we eat, wherever we pray upon the face of the earth, we shall uphold the first peoples of that place, those who have loved it longest and know its ways most deeply. We shall listen to them, learn from them, follow their lead, defend them, and join with them to protect each other and our world, and of every two grains in our bowls, we will give one to the first peoples who sit beside us at the earth’s table.

The names of those who were here before us are syllables of the earth’s name, so know them and speak them, and speak the first names for the places where you dwell, the water you drink, the winds that bring you breath. Say the name of this place, which is Shikaakwa, and say the names of its people: Myaamiaki, Illiniwek who are also the Inoca, the Asakiwaki and Meskwaki, people of the yellow earth and the red earth, the Hochagra, and the Bodewadmi who keep the hearth fires, for the land held many stories before we came and the places that were made for us were made by shattering their worlds.

Take to heart these words with which I charge you this day. Cherish this land beneath your feet. Cherish the roots and the waterways, the rocks and trees, the ancestor bones in the ground and the people who dance on the living earth and make new paths with their feet, with their breath, with their dreaming. Love and serve this world, this creation, as you love the creator who gifted it to us. Defend it from those whose hunger for riches cannot be filled, who devour and destroy, bringing death to everything we love.

Fight for the earth and protect it with all your heart and soul and strength, and hold nothing back, so that the rains fall in their season, the early rain and the late, and we may gather in the new grain and the wine and the oil, the squash and beans and corn, the apples and grapes and nuts, so that the grass grows high in the fields and feeds the deer and the cattle, so that the water flows clean in river and lake, filled with abundant fish, and birds nest among the reeds, and all that lives shall eat its fill.

Do not be lured into the worship of consumption, comfort, convenience. Do not suck on the drinking straws of extraction, or bow down to the hoarders of what is good. For if we do, the breath of life that is in all things will empty the skies of clouds, and there will be no rain, and the earth will not yield its blessings, but will be laid waste.

So summon all the courage which is in you and in your people, stretching back to the dawn of time and remember this promise by night and by day, with every breath, whatever you are doing. Let nothing stand in your way. Put your hands into the soil of this moment and plant good seed that we and all our children may live long in the land and be a blessing. 31

31 This prayer was written as part of Morales’ Rimonim Liturgy Project, a network of which Tzedek Chicago is a participating member. Rimonim seeks the creation of new liturgies that reflect, among other things, “a full integration of the lives and experiences of Indigenous Jews and Jews of Color of all backgrounds, diaspora-centered Judaism that is rooted in global Jewish cultures, and explicitly replaces Zionist content in our liturgy… and acknowledgement and accountability to Indigenous peoples on whose land non-Indigenous Jews are settlers.”

Conclusion

In her analysis of Tzedek Chicago, Omer referred to our congregation as a “prefigurative Jewish community.” 32 I believe this to be an extremely apt description: Tzedek Chicago is part of a nascent movement that is consciously attempting to build and model a future Jewish community guided by the transformative core values of justice that we hold sacred. In the end, however, it is not only the Jewish world we seek to transform – it is the world at large.

This idea is perhaps most prominently expressed during our Shabbat celebrations, when we liturgically welcome the Sabbath as a weekly taste of olam ha’ba (“the “world to come.”) 33 As opposed to the traditional messianic view of this concept, we define it as “the world as it should be” – i.e., the very real world of equity and justice for which we work and strive and struggle during the week. When Shabbat arrives, our liturgy provides us with the opportunity to experience this world, so that when Shabbat ends, we will be reinspired, replenished – and ready to continue the sacred work that will bring it that much closer to reality.

With this vision in mind, I will conclude with one final prayer – Tzedek Chicago’s poetic rendering of Psalm 92 (The Song for the Sabbath Day):

Tonight we raise the cup,

tomorrow we’ll breathe deeply

and dwell in a world

without borders, without limit

in space or in time,

a world beyond wealth or scarcity,

a world where there is nothing

for us to do but to be.

They said this day would never come,

yet here we are:

the surging waters have receded,

there is no oppressor, no oppressed,

no power but the one

coursing through every living

breathing satiated soul.

Memories of past battles fading

like dry grass in the warm sun,

no more talk of enemies and strategies,

no more illusions, no more dreams, only

this eternal moment of victory

to celebrate and savor the world

as we always knew it could be.

See how the justice we planted in the deep

dark soil now soars impossibly skyward,

rising up like a palm tree,

like a cedar, flourishing forever

ever swaying, ever bending

but never breaking.

So tonight we raise the cup,

tomorrow we’ll breathe deeply

to savor a world recreated,

and when sun sets once again

we continue the struggle.

32 Omer, p. 155.

33 From the Babylonian Talmud, Berachot 57b: “Shabbat is one sixtieth of the world to come.”