It’s difficult to describe the feelings I experienced this past weekend, as I watched hundreds of thousands of Gazans in a long and seemingly endless line, heading on foot to their homes in the north. Crossing the Netzarim corridor – the border the Israeli military demarcated separating north from south – they headed back with whatever possessions they were able to carry. Family members who thought each other dead clutched each other in tearful embrace. It was truly a wonder to behold: this resilient people who had defied and withstood the most destructive miliary onslaught in modern times. As Gazan activist Jehad Abusalim put it:

Gaza today, for now, disrupts and defies the global agenda of rendering entire populations disposable and rightless. This was achieved through the resilience of an entire population that has endured months of displacement, starvation, disease and bombardment.

Though this is a fragile and temporary ceasefire, it’s striking to note the depth of Israel’s failure to achieve any of its stated objectives of its genocidal war. It failed to destroy Hamas and the Palestinian armed resistance in Gaza. It failed to rescue hostages taken on Oct. 7 through military means. It failed to implement its so-called “General’s Plan” – its blueprint for ethnically cleansing northern Gaza. And perhaps most importantly, it failed to break the will of the Gazan people to survive its genocidal war.

Jehad’s words “for now” are appropriate. The overwhelming number of Gazans are returning to homes that are rubble – and it is by no means certain how they will be able to rebuild their lives. The ceasefire is a tenuous one; there is still no agreement on the second or third phases of deal and there is every possibility that Netanyahu will use the deal as cover to eventually depopulate Gaza of Palestinians. Trump’s recent comments (“I’d like Egypt to take people, and I’d like Jordan to take people…we just clean out that whole thing”) have made his intentions clear, even if his plan has been rejected outright by Arab states.

As I read the reports and analyses in the wake of this ceasefire, one thing seemed consistent to me: as ever, there is little, if any, concern for the humanity of the Palestinian people. On the contrary, every pronouncement by Western governments and the mainstream media treats their mere existence as a problem to be dealt with. In this regard, Jehad’s reference to “the global agenda of rendering entire populations disposable and rightless” is spot on. Palestinians in general – and Gazans in particular – have always been the canaries in the coal mine when it comes to the use of state violence against “problematic populations” deemed “disposable” by authoritarian states seeking to consolidate their power.

“Entire populations rendered disposable and rightless” certainly applied to events in my hometown of Chicago this past Sunday, where the Trump launched “Operation Safeguard,” a shock and awe blitz spearheaded by ICE, the FBI, ATF, DEA, CBP and US Marshals Service. Led by Trump’s so-called “border czar” Tom Homan (and surreally videotaped live by “Dr” Phil), heavily armed and armored forces terrorized Chicago neighborhoods all day, mostly going door to door, staking out streets in search of undocumented people, taking them away in full-body chains. While there is no definitive information on the numbers of people taken, federal immigration authorities claim to have arrested more than 100 people in recent days.

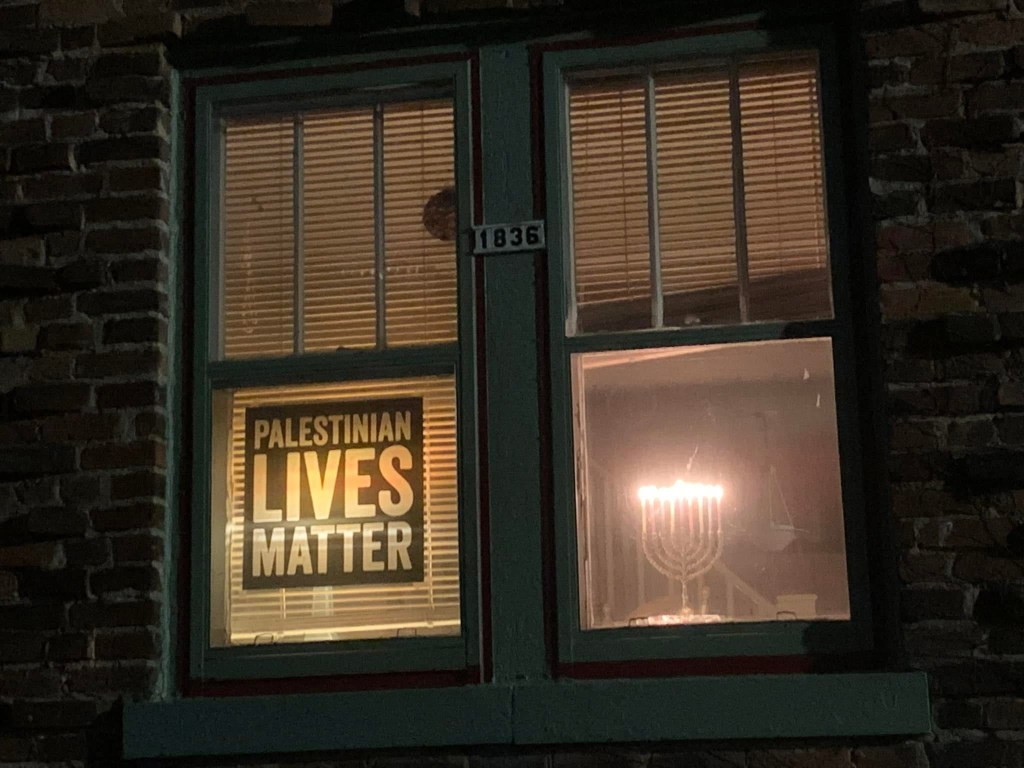

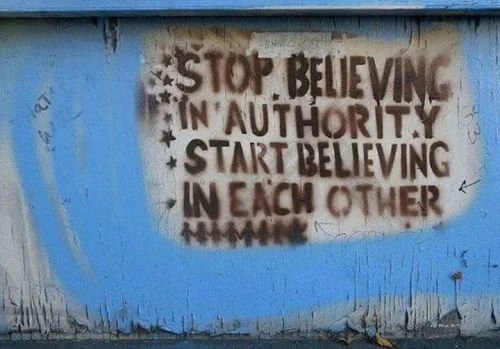

On a positive note, however, we are seeing that the strategies employed by local immigrant justice coalitions are making a real difference. My congregation, Tzedek Chicago is part of a local interfaith coalition called the Sanctuary Working Group, which has been mobilizing Know Your Rights trainings and Rapid Response teams. From our experience in Chicago over these past few days, we’ve seen that this kind of mobilization really does have an impact. Perhaps the strongest validation of these resistance strategies came from Homan himself, who said on an interview with CNN:

Sanctuary cities are making it very difficult to arrest the criminals. For instance, Chicago, very well educated, they’ve been educated how to defy ICE, how to hide from ICE. They call it “Know Your Rights.” I call it how to escape arrest.

in my previous post, I wrote that “the current political moment has left many of us breathless.” But over the course of the last several days, we’ve seen it is indeed possible “to disrupt and defy the global agenda of rendering entire populations disposable and rightless.” If we had any doubt at all, let us take our inspiration from the Gazan people, who have refused to submit after 15 months of merciless genocidal violence and are returning to their homes, vowing to rebuild and remain.

The most powerful shock and awe in the world could not break them. Let this be a lesson to us all.