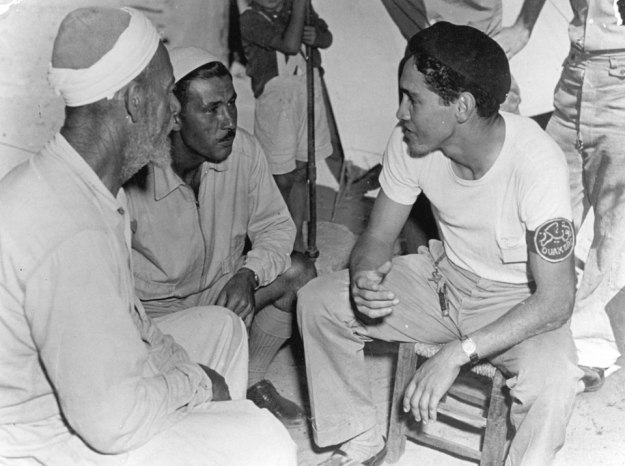

AFSC volunteer Evan Jones meeting with Palestinian refugees, 1949 (photo: AFSC)

Cross-posted with Acting in Faith.

Last Sunday, Israel revealed their list of 20 social justice groups from around the world it was henceforth banning from the country because of their support for the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement. For me, the list represented more than just another news item of the day. As staff person for one organization included on the list – the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) – this news struck home personally as well as professionally

As a rabbi who works for AFSC, I’m proud of the important historical connections between Jewish community and this venerable Quaker organization. As the US Holocaust Memorial Museum itself has noted, AFSC was at the forefront of efforts to help and rescue Jewish refugees after 1938, “ assisting individuals and families in need… helping people flee Nazi Europe, communicate with loved ones, and adjust to life in the United States.”

The USHM has also acknowledged that “the AFSC helped thousands of people in the United States transfer small amounts of money to loved ones in French concentration camps (and helped) hundreds of children, including Jewish refugees and the children of Spanish Republicans, come to the United States under the care of the US Committee for the Care of European Children in 1941–42.”

AFSC became involved with a different group of refugees – the Palestinians – several years later. At the end of 1948, while military hostilities in Palestine were still raging, the UN asked the AFSC to help spearhead the relief effort in Gaza, which was rapidly filling up with Palestinian refugees. Historian Nancy Gallagher has noted refugee relief was not the ultimate goal of their work in Gaza – rather, they “had accepted the invitation to participate in the relief effort with the expectation of assisting in the repatriation and reconciliation process.” (from “Quakers in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Dilemmas of Humanitarian Activism,” p. 97)

In March 1949, AFSC Executive Secretary Clarence Pickett offered a six-point plan to solve the refugee problem, urging “a substantial repatriation of Arabs into the State of Israel.” (p. 103) However, when it became clear that there was no international will for a political solution to the Palestinian refugee problem, AFSC formally stated that it wished to withdraw from Gaza, stating that “prolonged direct relief…militates against a swift political settlement of the problem.” (p. 104)

I have long been dismayed at the hypocrisy of those who applaud the Quakers’ work on behalf of Jewish refugees, yet bitterly criticize them for applying the very same values and efforts on behalf of Palestinian refugees. In a recent article for Tablet, for instance, Asaf Romirowsky and Alexander Joffe, made the spurious accusation that AFSC “has gone from saving Jews to vilifying them,” claiming that AFSC’s experience in Gaza convinced them to “get out of the relief business altogether” in order to promote “progressive Israel-hatred.”

In light of such invective, it’s not surprising to learn that Romirowsky and Jaffe are both professionally connected to the Middle East Forum – a notoriously Islamophobic radical right organization led by Daniel Pipes that has been categorized as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center. Beyond the nasty rhetoric however, it bears noting that AFSC has never been solely a relief organization. From its inception 100 years ago in the wake of WW I, it has consistently promoted reconciliation and repatriation alongside direct service to peacefully address conflicts around the world. AFSC’s work in Gaza was/is no exception.

Romirowsky and Jaffe further reveal their prejudiced agenda when they suggest that Palestinian refugees only wanted “to be maintained at someone else’s expense until Israel disappeared.” In fact, the AFSC’s refugee relief efforts in Gaza took place while Palestinians were actively being driven from their homes and were being housed in hastily constructed refugee camps. It is patently outrageous to suggest that they were motivated by anything other than their desire to return to their homes. Under such circumstances, it was not at all unreasonable for the AFSC to advocate for their return and repatriation.

In their article Romirowsky and Jaffe also parrot the Israeli government’s accusation that the BDS movement is “opposed to Israel’s existence.” What they refer to as “the BDS movement” is in fact a response to a call issued by a wide coalition of Palestinian unions, political parties, refugee networks, women’s organizations, professional associations, popular resistance committees and other Palestinian civil society bodies in 2005. The BDS call is a crie de cour from Palestinians to the world to use this time honored nonviolent strategy to pressure Israel to meet three essential demands:

- To end the occupation and colonization of the West Bank and Gaza and dismantle the separation wall;

- to recognize the fundamental rights of Arab-Palestinian citizens of Israel to full equality;

- and to respect, protect and promote the rights of Palestinian refugees to return to their homes and properties as stipulated in UN Resolution 194.

Although BDS is an inherently nonviolent tactic, it is striking to note the lengths to which the government of Israel has devoted time, energy and resources in trying to defeat it over the past decade. It has spent literally hundreds of millions of dollars to this effort, enlisted a myriad of Israel advocacy organizations and has even created a new government ministry devoted exclusively to fighting BDS. And though demands of the BDS call are based in human rights and international law, it is routinely referred to as antisemitic “economic terrorism” that “delegitimizes the state of Israel.” The blacklist of organizations is thus only the latest in a long line of draconian, non-democratic responses to this rapidly growing non-violent resistance movement.

As such, AFSC’s support of BDS is fully in keeping with its 100-year-old mission. As their recent organizational statement put it:

All people, including Palestinians, have a right to live in safety and peace and have their human rights respected. For 51 years, Israel has denied Palestinians in the occupied territories their fundamental human rights, in defiance of international law. While Israeli Jews enjoy full civil and political rights, prosperity, and relative security, Palestinians under Israeli control enjoy few or none of those rights or privileges.

The Palestinian BDS call aims at changing this situation, asking the international community to use proven nonviolent social change tactics until equality, freedom from occupation, and recognition of refugees’ right to return are realized. AFSC’s Principles for a Just and Lasting Peace in Palestine and Israel affirm each of these rights. Thus, we have joined others around the world in responding to the Palestinian-led BDS call. As Palestinians seek to realize their rights and end Israeli oppression, what are the alternatives left to them if we deny them such options?

Quakers pioneered the use of boycotts when they helped lead the “Free Produce Movement,” a boycott of goods produced using slave labor during the 1800s. AFSC has a long history of supporting economic activism, which we view as an appeal to conscience, aimed at raising awareness among those complicit in harmful practices, and as an effective tactic for removing structural support for oppression.

This past October I traveled with other AFSC staff people to East Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza, for meetings with our staff there. Yes, our efforts in Israel/Palestine still continue. While we do not yet know this latest action will impact our work, we are well aware that hundreds of thousands of Palestinians have been denied entry into the land of their ancestors for decades. The AFSC, like the other organizations on Israel’s odious list, know that peace can only come to this land when the essential injustice that occurred 70 years ago is justly addressed, and the human rights of all are recognized and respected.