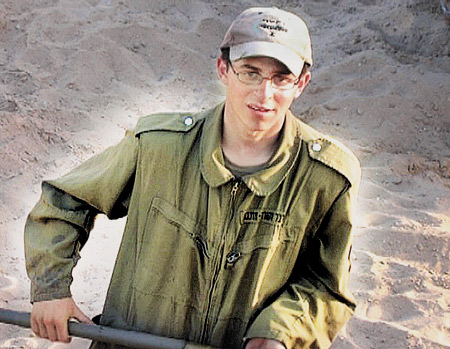

Not long ago I was asked by a friend: why are Israelis and Jews so fixated on the kidnapping of Gilad Shalit? With all of the crises and injustices being committed in the world, why is there such a hue and cry over this one particular man?

Not long ago I was asked by a friend: why are Israelis and Jews so fixated on the kidnapping of Gilad Shalit? With all of the crises and injustices being committed in the world, why is there such a hue and cry over this one particular man?

I answered that like all nations, Israel takes this kind of thing personally. I mentioned that just like many Jews in Israel and around the world, I also experienced Hamas’ abduction of Gilad Shalit as an injustice committed against one of my own. Even as a Jew living in the comfort of my Evanston home, I felt a visceral sense of pain three years ago when I first heard the news of Shalit’s kidnapping. Over time, my pain turned to anger as Hamas denied him Red Cross visits and refused to confirm (until only recently) whether he was even dead or alive.

I went on to compare Israel’s trauma to the feeling of collective trauma we felt in our country in 1979, when Iranian militants took American embassy workers hostage: how violated our nation felt: how personally we identified with the hostages; how deeply we experienced the injustice of their imprisonment.

On a less tribal level, of course, I do understand that there was a deeper context to the hostage crisis. Underneath our feelings of personal violation were more challenging questions – questions few of us were prepared to ask out loud. Why, for instance, did we have so much concern over 53 fellow Americans, but not for countless other political prisoners around the world, many of them incarcerated by regimes actively supported by our nation?

In just the same way, I believe too few Jews even know – let alone protest – that while Hamas unjustly imprisons Shalit, Israel holds hundreds of Palestinians taken in operations that at best must be considered ethically dubious. While Israel defends its actions legally by terming these prisoners “enemy combatants,” the hard truth remains that for decades Israel’s security services have rounded up scores of Palestinians without charge and have imprisoned them indefinitely – in many cases for years.

Yes, many of the prisoners are undoubtedly guilty of plotting or carrying out violent acts against Israelis. Many of these incarcerations can surely be defended on grounds of security. But it has become impossible to ignore that Israel has also incarcerated considerable numbers of Palestinians who by any reasonable definition must be considered political prisoners.

(One recent case in point: many Jews are familiar with the case of Gilad Shalit, but I’m sure that far fewer know, for instance, about Abdallah Abu Rahmah, a Palestinian high school teacher and coordinator of the non-violent campaign in the West Bank village of Bil’in, who was arrested last week by the Israeli military. According to eyewitness accounts, Abu Rahmah was taken from his bed at 2:00 am in the presence of his wife and children.)

And so, beyond the emotions of tribalism, the question remains: will we ever be able to see past our own loyalties and find equal value in the lives of others – human beings who are just as eminently worthy of fair treatment, justice and dignity? And even more challenging: will we ever be ready to admit that the violence committed against us is often inspired in no small way by the injustices we ourselves have committed – and continue to commit?

To return to the Iranian hostage example: back in 1979, few Americans cared to even ask why their Iranian captors might have been so motivated to commit this act. Most of us were ignorant to the powerful significance of the American embassy for Iranians – that it was this very same embassy from which our nation had plotted the overthrow of Iran’s democratically elected government in 1953. As it turned out, the regime we subsequently installed would persecute and unjustly imprison countless Iranian citizens over the next two decades.

So too in the case of Gilad Shalit. Few of us in the Jewish community are truly ready to examine the source of Gazan’s fury toward Israel – a fury that has been building since long before Hamas even existed. Few of us are willing to face the history of Israel’s oppressive policies in Gaza or the fact that Gazans have been living under an intolerable occupation for decades.

And even fewer of us even know that the overwhelming majority of the 1.5 million who live in Gaza belong to families that originally came from outside of Gaza – from towns and villages like Ashkelon and Beersheba – and were expelled from their homes by the Israeli military in 1948. Indeed, when I think of Gazan rage in 2009, I can’t help but think of these chilling words by Moshe Dayan from back in 1956:

Who are we that we should bewail their mighty hatred of us? (They) sit in refugee camps in Gaza, and opposite their gaze we appropriate for ourselves as our own portion the land and the villages in which they and their fathers dwelled.

The history of Gaza is indeed a tragic one – and yes, Israel’s oppression of its population is a critical part of this tragedy. Unless we take the time to understand this history – and our part in it – I don’t believe we can even begin to pretend there is a way out of this conflict.

To be clear: understanding the source of Gazans feelings toward Israel does not mean condoning their actions. Hamas’ imprisonment of Gilad Shalit is barbaric. As a fellow Jew, I grieve for Shalit and I pray for his safe return. But at the same time, I cannot look away from the more painful realities that led to his capture in the first place, and I truly believe that until we make an honest effort to face and address these realities, there will invariably be more Gilad Shalits in Israel’s future.

Following Israel’s military campaign in Lebanon in the summer of 2006, journalist Amira Hass wrote these powerful words in Ha’aretz. I believe she presents us with a profound model of an Israeli who is able to hold her own concern for her people together with a willingness to face the truth of the injustices perpetrated her nation. Her words are doubly tragic as we now approach the one-year anniversary of Israel’s military campaign in Gaza:

We are justly concerned about the welfare of northern residents, proud of their fortitude, understand those who leave, are shocked by the death of each person and by every rocket hit, and identify with those suffering from anxiety. Take what the northern residents have been going through for a month, multiply it by 1,000, add an economic blockade, power and water cuts, and no wages. This is how the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip have been “living” for the past six years.

The Israelis allow their army to continue destroying, trampling and killing in the Palestinian territories. Here, like in Lebanon, the real intelligence and security failure is Israel’s ignoring the extent of our uninhibited, unrestrained devastation and their amazing power of human endurance. This is why Israel has delusions of “victories.” If the homemade rockets are still being fired at Sderot despite the Palestinians’ extensive suffering, it is because they have concluded, correctly, that Israel’s destruction power is not intended to stop Qassam rockets – or to free Gilad Shalit. It is intended to force them to accept a surrender arrangement, which they reject not with military victories but with their power of endurance.

Well put. The negotiations over Shalit has given plenty of support to the idea that Israel understands only force and values the lives of its own citizens many times that of the Palestinians it holds without trial (same as the US unfortunately) . If it is willing to negotiate Shalit’s release as I believe it should, then it should be willing to negotiate a just end to the conflict. .

What a brilliant and important post! I think you have penetrated the heart of the human tendency to focus on our own rather than on the fate of everyone. You challenge us so powerfully to transcend our tribalism. This article should be widely disseminated, I hope many Jews get the opportunity to read it.

Thank you, my dear friend and colleague, for your wisdom and courage.

Good Post. One aspect that I think needs clarification after reading some of the replies is the tendency for us to place a greater importance on “our own” than on the “other”. Is it not normal to love our family and friends more than the stranger? Doesn’t this fact allow for the family unit and our communal identity as Jews? If everyone loved each other equally there would be a breakdown in society as we know it (perhaps this is how peace on earth would look like). But is this actually what we are contemplating here? Do we really mean to love the stranger(ie Palistinean) as we’d love our family?

I would argue that the family unit and the concentric social circles that extend outward from it including friends and then other Jews, is the mechanism that allows for us to learn HOW to love and because of it gives us the ability to extend that to the stranger, not in spite of it. We should not denigrate this fact but hope that our connections with these circles allows us to develop the required empathy those strangers deserve.

I’m not as fond as Brant of scripture-based arguments, but here’s one where the Torah offers a bit of guidance.

David asks, “do we really mean to love the stranger as we’d love our family”? The imperative comes from Deut. 10: 19, but the reasoning–and the “as,” the equivalent, the point of comparison–is somewhat different: “Love the stranger, for you were once strangers in the land of Egypt.”

It’s not that we should love the stranger as we’d love our family, then. (Which can be a vexed, love / hate kind of relationship, Lord knows.) Rather, we should love the stranger as we wish we had, ourselves, been loved when we were in his or her shoes.

Which is not, perhaps, “normal,” but it might be helpful.

Universal love and sympathy are important for civilised human society. But who can blame Israelis for concentrating on their own people first? But there is a very disturbing sign: some Israelis believe that not only Hamas but their own government as well is not sincere in its efforts to free Gilad through negotiations. Here’s the link to an article with this view:

http://samsonblinded.org/news/shalit-talks-drowned-in-hypocrisy-15345