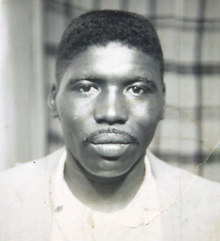

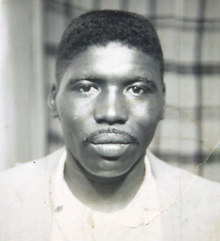

Jimmie Lee Jackson

I’d like to begin tonight by telling you the stories of three heroes of the civil rights era. I’d wager most Americans have never heard of them – but as far as I’m concerned, they deserve to be at least as well known as Emmett Till, Medger Evers and Rosa Parks.

The first is Jimmie Lee Jackson, an African-American farmer and woodcutter from in Marion, Alabama. Jackson grew up in poverty, but planned to move North for a better life after graduating from high school. After his father’s early death however, he spent his the remainder of his life on his small family farm in Marion, where he lived together with his sister, mother, and grandfather.

Jackson was an army veteran and a deeply faithful man; he became the youngest deacon in the history of Marion’s St. James Baptist Church. He also turned into a political activist at an early age after unsuccessfully attempting to register to vote for four years. Jackson spearheaded his church’s voter registration drive and eventually became a prominent civil rights leader in Merion.

On the night of February 18, 1965, Jackson participated in a demonstration in which 500 people peacefully marched from a church in Marion to the county Jail about a half a block away to protest the imprisonment of a young civil rights worker. On their way, the marchers were met and beaten by a line of Marion City police officers, sheriff’s deputies, and Alabama State Troopers. Among the injured were two United Press International photographers. A NBC News correspondent was so badly beaten that he was later hospitalized.

The marchers quickly turned and scattered back towards the church. Pursued by the state troopers, Jackson, his sister, mother, and 82-year-old grandfather ran into a café. The troopers followed them in and clubbed his grandfather to the floor. When Jackson’s sister and mother attempted to pull the police off and they began to beat them as well. Jackson went to protect them and a trooper threw him against a cigarette machine. A second trooper moved in and shot Jackson twice at point blank range in the abdomen.

Jackson staggered outside, was clubbed again and fell wounded in the street, where he lay for half an hour. Later that night, Jackson, his mother and grandfather were transported to a hospital in Selma. His mother and grandfather suffered head wounds but were treated and released – Jimmie Lee remained in the hospital where his condition grew steadily worse. Four days later, an Alabama state trooper walked into and hospital room and charged Jackson with assault and battery with intent to murder a peace officer. Eight days later, on Friday, February 26, Jimmie Lee Jackson died from his wounds.

His funeral took place on March 3. Dr. Martin Luther King was among the speakers at the service, after which a thousand people followed Jackson’s casket through the rain to a local cemetery. Four days later, several hundred marchers left Brown Chapel in Selma, formed a long column, and began walking up the steep incline of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which spans the Alabama River. Their goal was to walk 54 miles to the state capitol in Montgomery to protest Jackson’s death and petition the governor and legislature to open the state’s voting rolls to all citizens. The march ended violently on a day we would all come to know as “Bloody Sunday.” It was a galvanizing moment in the fight for voting rights in this country.

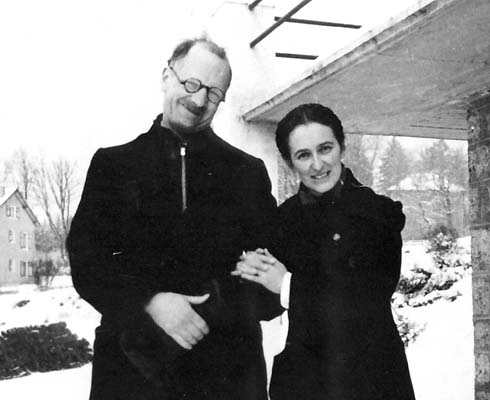

Reverend James Reeb

The second person I’d like to profile for you now is Reverend James Reeb. Reeb was raised in Caspar, Wyoming, served in the Army during World War II, and was later ordained by the Princeton Theological Seminary. Soon after, however, he left the Presbyterians and joined the Unitarian Universalist church. As a white man who believed in civil rights, he was particularly drawn to the UU’s strong emphasis on social justice.

Reverend Reeb was fully ordained as a Unitarian Universalist minister in 1962. After serving for a few years at All Souls Church in Washington DC, he became the director of the American Friends Service Committee Metropolitan Boston Low Income Housing Program in 1964. With his wife and four children, he moved to Boston and purchased a home in Roxbury, a predominantly African-American area of the city. His daughter Anne later recalled that her father “was adamant that you could not make a difference for African-Americans while living comfortable in a white community.”

Following Bloody Sunday, Reeb went down to Selma with 45 Unitarian ministers and 15 laypeople to participate in the voting rights demonstrations that arose in the wake of Bloody Sunday. On March 9, he joined 2,500 marchers for a second march from Selma to Montgomery. As on previous attempts they were stopped by the police – and so the marchers returned to Browns Chapel for an evening of speeches, singing and prayers.

Later that night, Reeb and two other Unitarian ministers had dinner in a local black restaurant. Although he had planned to return to Boston that night, he called his wife and told her he had decided to stay for one more day. Upon leaving the cafe, the trio was set upon by four men brandishing clubs and yelling racist slurs. They attacked and beat the three men – wounding his two colleagues and severely injuring Reeb with a blow to his skull. Needing a neurosurgeon, he was driven ninety miles by ambulance to University Hospital in Birmingham. He died two days later.

Reverend James Reeb’s death sparked mourning event throughout the country – tens of thousands held vigils in his honor, including a ceremony in Selma, where he, like Jimmie Lee Jackson, was eulogized by Dr. King. That evening, on March 15, President Johnson spoke to a joint session of Congress on behalf of the Voting Rights Act. It was his famous “We Shall Overcome” speech, in which he urged Congress to outlaw all voting practices that denied or abridged “the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.” Six months later, Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law.

Viola Liuzzo

And finally, let me tell you now about Viola Liuzzo – born in 1925 to a poor white family that moved constantly throughout the Deep South. During the early months of World War II, her family moved to Michigan, where she worked in a bomber factory. Eager to contribute to the war effort herself, Viola moved to Detroit, where she married and had two daughters. They divorced shortly after and she eventually married Anthony James Liuzzo, a union organizer for the Teamsters. Anthony adopted her daughters and they had three more children together.

Though she was a high school dropout, Liuzzo trained as a medical laboratory assistant and later took classes at Wayne State University. There she was exposed to political ideas of the time, including debates about the Vietnam War, education reform, and economic justice. This period marked the beginning of her political activism. She was arrested twice in demonstrations and both times she insisted on a trial in order to publicize her causes.

In 1964 Liuzzo, a former Catholic, joined the First Unitarian Universalist Church of Detroit – attracted, like Reverend Reeb, by its commitment to civil rights. She also became active in the Detroit chapter of the NAACP. Like so many others, Liuzzo was galvanized by events in Selma. Following Reverend Reeb’s murder she attended a memorial service for him and soon after, she decided to go down to Selma herself to volunteer for a week. As she explained to her husband, she believed there were “too many people who just stand around talking.” She asked her closest friend, an African-American woman named Sarah Evans, to explain to her children where their mother had gone and to tell them she would call home every night. When Evans warned her that she could be killed, she replied simply, “I want to be part of it.”

So on March 21, Liuzzo joined 3,000 other marchers as they marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge attempting to reach Montgomery. She stayed on to volunteer over the next few days, driving shuttle runs from the airport to the marchers’ campsite and helping at a first-aid station.

On March 25, she joined the marchers for the final four miles to Montgomery, where she joined the thousands that demonstrated at the Alabama State House. When the march was over, Liuzzo and African-American civil rights worker named Leroy Moton drove five marchers back to Selma. After they were dropped off, Viola volunteered to return Moton to Montgomery. On their way back, four Ku Klux Klan members pulled up alongside their car. Liuzzo tried to outrun them, but they caught up with her car and opened fire. Viola was shot twice in the head and died instantly.

Following her murder, President Johnson publicly demanded that the arrest of Liuzzo’s murderers be a top priority. In just 24 hours, the FBI arrested the four Klan members, one of home was an FBI informant. Johnson appeared personally on national television to announce their arrest.

The FBI would later attempt to publicly discredit Liuzzo – most likely to cover up the fact that their agent was a KKK member and may have actively participated in her murder. J. Edgar Hoover personally spread rumors that Liuzzo was a member of the Communist party and a drug addict and that she had traveled to Selma to have sexual relations with black men. Viola’s family was also targeted by hate groups – after crosses were burned in front of their home. Anthony Liuzzo had to hire armed guards to protect his family.

However, as in the case of Jimmie Lee Jackson and Revered James Reeb, Viola Liuzzo’s death had a powerful impact on the voting rights movement across the country. On March 27 hundreds of protesters marched to the Dallas County courthouse in Selma in her memory. The next day Dr. King eulogized her at San Francisco’s Grace Episcopal Cathedral. The NAACP also sponsored a memorial service for Liuzzo at a Detroit church that was attended by fifteen hundred people including Rosa Parks. A Roman Catholic Church in Detroit celebrated a high requiem mass that was broadcast on TV. Dr. King was among the 750 people in attendance.

As with Jackson and Reeb, Viola Liuzzo’s murder played a critical role in the eventual passage of the Voting Rights Act. According to historians, Johnson invoked her death repeatedly as he lobbied Congress. Five months after she died, he signed it into law.

Why am I telling you the stories of these three individuals tonight? One simple reason is that I believe they deserve to be told. We owe Jimmie Lee Jackson, Reverend James Reeb and Viola Liuzzo at least that much. And we owe it to ourselves. I took the time to tell you about them because so few really know the stories of these American heroes. And we should. We should know who they were, how they lived and the significance of their sacrifice.

I also have a specifically liturgical reason for telling you their stories tonight of all nights. The traditional Yom Kippur service includes a section known as the Martyrology (or as we call it in Hebrew, “Eleh Ezkarah,” meaning “These I Remember.”) The centerpiece of Martyrology is a long liturgical poem that recounts the death of ten rabbis – including the famous Rabbis Akiba, Ishmael and Shimon ben Gamliel – who were executed for their support of the failed revolt against Rome in the year 132.

We traditionally read these accounts on Yom Kippur because of the classical Jewish belief that blood atones. Our Torah portion tomorrow will, in fact, describe an ancient sacrificial rite of atonement, in which the High Priest sacrifices a goat on behalf of the entire Israelite people. Though the sacrificial system is no more, we ask for God’s forgiveness by invoking the deaths of those who made the ultimate sacrifice. And so on Yom Kippur, we beseech God: even if we are unworthy of God’s mercy in the coming year, we ask for forgiveness us on account of those who made the supreme sacrifice on our behalf.

Whether or not we buy into such a theology, I believe the Martyrology has an additional function as well: on Yom Kippur we pose the question honestly: what have we done in the past year to prove ourselves worthy of these profound sacrifices? What have we done to affirm that these courageous people did not die in vain? Have we honored their memories by transforming these lost lives into justice, hope and healing for our world?

When we ask these questions as 21st century American Jews, I believe they resonate for us on multiple levels. When we invoke those Jews who died for practicing their faith, we must ask: have we done what we can to ensure that this Judaism – this exquisite spiritual tradition of ours – will be passed on to future generations? And as Americans, when we remember those who died in furtherance of justice in our country, we are challenged: how have we honored their sacrifice? What to have we done in the past year to ensure that they did not die in vain?

Indeed, at the heart of this liturgy is a refusal to accept that our martyrs have died for nothing. I’ve just recounted for you the stories of three lesser-known martyrs of the American civil rights movement – but this Sunday, as a matter of fact, we will commemorate the 50th anniversary of four others who are much better-known: Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley – the four little girls who were killed by a KKK bomb in Birmingham’s 16th St. Baptist Church on September 15, 1963.

At the funeral for three of the girls, Dr. King gave a famous address that has since come to be known as the “Eulogy for the Martyred Children.” At one point in his eulogy, King said as follows:

So they did not die in vain. God still has a way of wringing good out of evil. History has proven over and over again that unmerited suffering is redemptive. The innocent blood of these little girls may well serve as the redemptive force that will bring new light to this dark city … The spilt blood of these innocent girls may cause the white citizenry of Birmingham to transform the negative extremes of a dark past in to the positive extremes of a bright future. Indeed, this tragic event many cause the white South to come to terms with its conscience

Amongst the many religious texts I’ve read on the meaning of martyrdom, I personally find King’s words to be among the most spiritually meaningful and profound. I am particularly moved by his hope, by his realism, but most of all, by his refusal to surrender to the possibility that these four little girls died for nothing. Even in the midst of this wretched tragedy, he was determined to find a spark of spiritual meaning in their loss.

In his eulogy, King also described of blood of the martyrs as redemptive – but he did so in a way that affirmed goodness and justice in the face of an evil, unjust act. As horribly tragic as their deaths were, King could not help but affirm that their deaths would, as he put it, “serve as a redemptive force” that would eventually bring new light during those very dark days. And perhaps most important: his theology was not limited to mere words. As soon as he finished speaking, he continued to lead a movement that would ensure these sacrifices would bring social and political transformation to the American South.

In the end, I’m taking the time to tell you about Jimmie Lee Jackson, Reverend James Reeb and Viola Liuzzo because I believe their stories are utterly appropriate to this day. On Yom Kippur, as we bear witness to their lives, their work and their sacrifice, we are the recipients of a direct spiritual challenge. Now that we’ve heard their stories, it’s time to ask ourselves: have what have we done to carry on the work that they have left unfinished? Have we done all that we can to give their lives and their deaths meaning? Have we done everything in our power to ensure their deaths were not in vain?

Well my friends, we have a very real opportunity to find out, because these are not merely academic questions. Just three months ago, the US Supreme Court dealt a devastating blow to the very cause for which these three individuals sacrificed their lives. As I’m sure everyone here tonight knows, on June 25, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 to invalidate a key element of the Voting Rights Act – the section that required states with the worst history of voting discrimination to seek preclearance from federal government before implementing new voting changes.

Indeed, there have been numerous attempts to weaken or gut the Voting Rights Act over the past 50 years. Only a month after it was enacted, in fact, it was constitutionally challenged by South Carolina. Over the years, the Voting Rights Act has been challenged in the Supreme Court four separate times – in 1966, 1973, 1980 and 1999 – and each time, the Court has voted to uphold it. Meanwhile, the US Congress has voted to reauthorize the Voting Rights Act on four separate occasions; each and every time it was signed back into law by a Republican president.

In his ruling for the majority last June, Chief Justice John Roberts argued that there is no longer a need for the federal government to actively ensure voting rights:

Nearly 50 years later, things have changed dramatically. Largely because of the Voting Rights Act, (voter) turnout and registration rates in covered jurisdictions now approach parity. Blatantly discriminatory evasions of federal decrees are rare. And minority candidates hold office at unprecedented levels. The tests and devices that blocked ballot access have been forbidden nationwide for over 40 years.

According to this reasoning, voter suppression is simply not the problem it was back in 1965. As Justice Roberts put it, “the Nation is no longer divided along those lines yet the Voting Rights Act continues to treat it as it were.”

Justice Ruth Ginsberg,in a brave and blistering dissent to the majority, stated the patently obvious: the reason things have changed since 1965 because the Voting Rights Act has been in place since 1965. As she wrote:

Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.

If there could be any doubt to Justice Ginsberg’s argument, her point has since been driven home with brutal clarity. Two hours after the ruling, officials in Texas announced that they would begin enforcing a strict photo identification requirement for voters, which had been blocked by a federal court on the grounds that it would disproportionately affect African-American and Hispanic voters. And as we speak, state officials in Mississippi, Alabama, North Carolina and Florida, among others, are now moving to change voter identification laws – laws that had previously been rejected as discriminatory by the federal government.

Make no mistake: this Supreme Court ruling has struck a devastating blow to voting rights in our country. And in so doing, it has reinforced a hard truth: it challenges us with a reminder that the struggle for justice is not a one-time moment but an ongoing process. Indeed, we are so very good at commemorating the victories of the past – but too often, it seems to me, we do it at the expense of the present. I do believe as King has famously said that the arc of freedom bends toward justice – but it doesn’t do so all by itself. Justice will only prevail if we remain vigilant. It is not enough to commemorate and teach our children about the heroes of the civil rights movement in ages gone by. On the contrary, we must teach that we ourselves must consistently do what we must to honor their achievements – and most importantly, their sacrifices.

On Yom Kippur, we ask: who has paid the ultimate sacrifice in the cause of righteousness – and what will we do in the coming year to honor their sacrifice? And on this Yom Kippur, I can think of no better spiritual gesture than to lend our support to the political efforts currently underway to restore the hard fought laws that ensure voting rights for all in our country.

At the moment, these efforts are taking many forms. Given the current reality in Washington, it is clear that our bitterly divided Congress is unable to legislatively address this issue. But there are other efforts ongoing that are eminently worthy of our attention and support. This past July, the Obama administration asked a federal court in Texas to restore the preclearance requirement there. In a speech to the Urban League, Attorney General Eric Holder said that this action is only the first of many different moves the Justice Department will make on behalf of voting rights throughout the country. A more ambitious effort: a Constitutional Amendment that would guarantee the right to vote, is currently being advocated by Wisconsin Congressman Mark Pocan and Minnesota’s Keith Ellison, among others.

In fact, there is no explicit right to vote spelled out in the US Constitution – and as a result, individual states continue to set their own electoral policies and procedures. At present, our electoral system is divided into 50 states, more than 3,000 counties and approximately 13,000 voting districts, all, in sense, separate and unequal. As Rep. Ellison has put it, “It’s time we made it clear once and for all: every citizen in the United States has a fundamental right to vote.”

Obviously passing a Constitutional amendment is a daunting prospect, but this campaign certainly has the potential to build a broad movement that would keep this issue front and center of our national consciousness. And such a movement could well create space for more immediate action at the congressional and state levels to address the devastating fallout from the Supreme Court’s ruling.

I frankly can think of no political actions more appropriate this Yom Kippur than this: actions that will bring redemption to the lives and deaths of Jimmie Lee Jackson, Reverend James Reeb and Viola Liuzzo. I hope you found meaning in their stories – and I fervently hope that we will all come to see ourselves as participants in their stories that continue to unfold even now.

I’d like to conclude with words from Reverend Reeb’s final sermon. They clearly have a heartbreaking significance when you hear them today – but I do believe they speak to us with as much urgency as the day he spoke them in All Souls Church in July 1964: At the very end of his sermon, Reverend Reeb said:

If we are going to be able to meet their need, we are going to have to really take upon ourselves a continuing and disciplined effort with no real hope that in our lifetime we are going to be able to take a vacation from the struggle for justice. Let all who live in freedom won by the sacrifice of others, be untiring in the task begun, till every man on earth is free.

This and every Yom Kippur, may we be worthy of his words.

(Click here to sign a petition that urges the Justice Department to block discriminatory voter ID laws in our country. Click here to contact your representative and demand Congress act now to pass a constitutional amendment guaranteeing the right to vote.)

Memorial for Jimmie Lee Jackson, Reverend James Reeb and Viola Liuzzo, UU Headquarters, Boston

And it is an oppression we saw for ourselves quite literally on a daily basis. It is difficult to do justice to the stifling atmosphere in these West Bank communities that are struggling so hard to live a semblance of normalcy amid the separation wall, the checkpoints, the ever-growing settlements, the night raids and the tear gas. As we saw for ourselves, their very steadfastness represents their purest form of resistance. As it is written in various points along the separation wall: “To Exist is to Resist.”

And it is an oppression we saw for ourselves quite literally on a daily basis. It is difficult to do justice to the stifling atmosphere in these West Bank communities that are struggling so hard to live a semblance of normalcy amid the separation wall, the checkpoints, the ever-growing settlements, the night raids and the tear gas. As we saw for ourselves, their very steadfastness represents their purest form of resistance. As it is written in various points along the separation wall: “To Exist is to Resist.”