Like you, I’ve been profoundly horrified by the refugee crisis that has resulted from Syria’s ongoing civil war. The reports and images and statistics continue to roll out every day and the sheer level of human displacement is simply staggering to contemplate. Since 2011, over half of that country’s entire population has been uprooted. At present, there are more than 4 million Syrian refugees are registered with the UN. Another 7 million have been internally displaced. Experts tell us we are currently witnessing the worst refugee crisis of our generation.

The tragic reality of forced migration has been brought home to us dramatically this past summer – but of course, this crisis did not just begin this year and Syria is not the only country in the region affected by this refugee crisis. Scores are also fleeing civil war and violence from countries such as Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan and Yemen. In all of 2014, approximately 219,000 people from these countries tried to cross the Mediterranean to seek asylum in Europe. According the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, in just the first eight months of 2015, over 300,000 refugees tried to cross the sea – and more than 2,500 died.

And of course this issue is not just limited to the Middle East. It extends to places such as Latin and Central America and Sub-Saharan Africa as well – and it would be not at all be an exaggeration to suggest that the crisis of forced human migration is reaching epidemic proportions. Just this past June, the UN High Commissioner on Refugees issued a report that concluded that “wars, conflict and persecution have forced more people than at any other time since records began to flee their homes and seek refuge and safety elsewhere.”

It is all too easy to numb ourselves to reports such as these – or to simply throw up our hands and chalk it up to the way of the world. But if Yom Kippur is to mean anything, I would suggest it demands that we stand down our overwhelm. To investigate honestly why this kind of human dislocation exists in our world and openly face the ways we are complicit in causing it. And perhaps most importantly to ask: if we are indeed complicit in this crisis, what is our responsibility toward ending it?

There is ample evidence that we as Americans, are deeply complicit in the refugee crises in the Middle East. After all, the US has fueled the conflicts in all five of the nations from which most refugees are fleeing – and it is directly responsible for the violence in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya.

In Iraq, our decade-long war and occupation resulted in the deaths of at least a million people and greatly weakened the government. This in turn created a power vacuum that brought al-Qaeda into the country and led to the rise of ISIS. Over 3.3 million people in Iraq have now been displaced because of ISIS.

In Afghanistan, the US occupation continues and we are war escalating the war there, in spite of President Obama’s insistence that it would end by 2014. According to the UN, there are 2.6 million refugees coming out of Afghanistan.

In Libya, the US-led NATO bombing destroyed Qaddafi’s government. At the time, then Secretary of State Clinton joked to a news reporter, “We came, we saw, he died.” Shortly after Libya was wracked with chaos that led to the rise of ISIS affiliates in northern Africa. Many thousands of Libyans are now fleeing the country, often on rickety smuggler boats and rafts. The UN estimates there are over 360,000 displaced Libyans.

In Yemen, a coalition of Middle Eastern nations, led by Saudi Arabia and backed by the US, has been bombarding Yemen for half a year now, causing the deaths of over 4,500 people. We continue to support this coalition, despite the fact that human rights organizations are accusing it of war crimes that include the intentional targeting of civilians and aid buildings. As a result, the UN says, there are now over 330,000 displaced Yemenis.

And the US is not free of responsibility for the crisis in Syria either. For years now, we have been meddling in that civil war, providing weapons to rebels fighting Assad’s government. But since the rise of ISIS the US has backed away from toppling his regime – and there are now reports that the US and Assad have even reached “an uncomfortable tacit alliance.”

Despite our role in the Syrian civil war, our government is taking in relatively few refugees from that country. Just last Monday, Secretary of State Kerry announced that the US would increase the number of refugees to 100,000 by 2017, saying “This step is in the keeping with America’s best tradition as land of second chances and a beacon of hope.” In reality, however, this number is still a drop in the bucket relative to the dire need – and only an eighth of the number that Germany has pledged to take in this year.

Kerry’s comment, of course, expresses a central aspect of the American mythos – but in truth it is one that flies in the face of history. While we like to think of ourselves “as a land of second chances and a beacon of hope,” these words mask a darker reality: it is a hope that only exists for some – and it has largely been created at the expense of others. Like many empires before us, our nation was established – upon the systemic dislocation of people who are not included in our “dream.”

If we are to own up to our culpability in today’s crises of forced human migration, we must ultimately reckon with reality behind the very founding of our country. The dark truth is that our country’s birth is inextricably linked to the dislocation and ethnic cleansing of indigenous peoples this land. It was, moreover, built upon the backs of slaves who were forcibly removed from their homes and brought to this country in chains. It is, indeed, a history we have yet to collectively own up to as a nation. We have not atoned for this legacy of human dislocation. On the contrary, we continue to rationalize it away behind the myths of American exceptionalism: a dream of hope and opportunity for all.

And there’s no getting around it: those who are not included in this “dream” – the dislocated ones, if you will – are invariably people of color. Whether we’re talking about Native Americans and African Americans, the Latino migrants we imprison and deport, or the Syrian, Iraqi, Afghani or Yemini refugees of the Middle East. If we are going to reckon with this legacy, we cannot and must not avoid the context of racism that has fueled and perpetuated it.

As a Jew, of course, I think a great deal about our legacy of dislocation. To be sure, for most of our history we have been a migrating people. Our most sacred mythic history describes our ancestors’ travels across the borders of the Ancient Near East and the Israelites’ wanderings in the wilderness. And in a very real sense, our sense of purpose has been honored by our migrations throughout the diaspora – yes, too often forcibly, but always with a sense of spiritual purpose. For centuries, to be a Jew meant to be part of a global peoplehood that located divinity anywhere our travels would take us.

Our sacred tradition demands that we show solidarity with those who wander in search of a home. The most oft-repeated commandment in the Torah, in fact, is the injunction against oppressing the stranger because we ourselves were once strangers in the land of Egypt. And given our history, it’s natural that we should find empathy and common cause with the displaced and uprooted.

However, I do fear that in this day and age of unprecedented Jewish success – and dare I say, Jewish privilege – we are fast losing sight of this sacred imperative. One of my most important teachers in this regard is the writer James Baldwin, who was an unsparingly observer of the race politics in America. In one particularly searing essay, which he wrote in 1967, Baldwin addressed the issue of Jewish “whiteness” and privilege in America. It still resonates painfully to read it today:

It is galling to be told by a Jew whom you know to be exploiting you that he cannot possibly be doing what you know he is doing because he is a Jew. It is bitter to watch the Jewish storekeeper locking up his store for the night, and going home. Going, with your money in his pocket, to a clean neighborhood, miles from you, which you will not be allowed to enter. Nor can it help the relationship between most Negroes and most Jews when part of this money is donated to civil rights. In the light of what is now known as the white backlash, this money can be looked on as conscience money merely, as money given to keep the Negro happy in his place, and out of white neighborhoods.

One does not wish, in short, to be told by an American Jew that his suffering is as great as the American Negro’s suffering. It isn’t, and one knows that it isn’t from the very tone in which he assures you that it is…

For it is not here, and not now, that the Jew is being slaughtered, and he is never despised, here, as the Negro is, because he is an American. The Jewish travail occurred across the sea and America rescued him from the house of bondage. But America is the house of bondage for the Negro, and no country can rescue him. What happens to the Negro here happens to him because he is an American.

In other essays, Baldwin referred to white immigrant success in America as “the price of the ticket” – in other words, the price for Jewish acceptance into white America was the betrayal of the most sacred aspects of our spiritual and historical legacy. We, who were once oppressed wanderers ourselves, have now found a home in America. But in so doing we have been directly or indirectly complicit in the systematic oppression and dislocation of others.

On Rosh Hashanah I talked about another kind of Jewish deal called Constantinian Judaism – or the fusing of Judaism and state power. And to be sure, if we are to talk about our culpability this Yom Kippur in the crime of forced migration, we cannot avoid reckoning with the devastating impact the establishment of the state of Israel has had on that land’s indigenous people – the Palestinian people.

According to Zionist mythos, the Jewish “return” to land was essentially a “liberation movement.” After years of migration through the diaspora, the Jewish people can finally at long last come home – to be, as the national anthem would have it, “a free people in their own land.”

The use of the term “liberation” movement, of course is a misnomer. It would be more accurate to term Zionism as a settler colonial project with the goal of creating an ethnically Jewish state in a land that already populated by another people. By definition the non-Jewish inhabitants of Palestine posed an obstacle to the creation of a Jewish state. In order to fulfill its mandate as a political Jewish nation, Israel has had to necessarily view Palestinians as a problem to somehow be dealt with.

Put simply, the impact of Jewish nation-statism on the Palestinian people has been devastating. The establishment of Israel – a nation designed to end our Jewish wanderings – was achieved through the forced dislocation of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their homes, which were either destroyed completely or occupied by Jewish inhabitants.

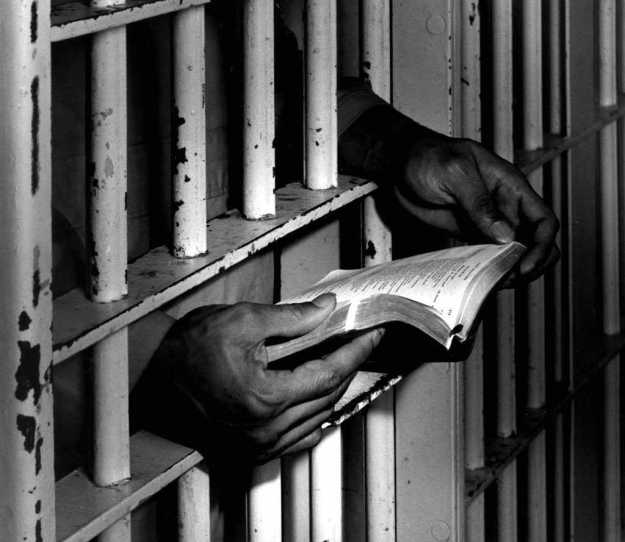

In turn, it created what is now the largest single refugee group in the world and our longest running refugee crisis. Millions of Palestinians now live in their own diaspora, forbidden to return to their homes or even set foot in their homeland. Two and a half million live under military occupation in the West Bank where their freedom of movement is drastically curtailed within an extensive regime of checkpoints and heavily militarized border fences. And nearly two million live in Gaza, most of them refugees, literally trapped in an open-air prison where their freedom of movement is denied completely.

This, then, is our complicity – as Americans, as Jews. And so I would suggest, this Yom Kippur, it is our sacred responsibility to openly confess our culpability in this process of uprooting human beings from their homes so that we might find safety, security and privilege in ours. But when then? Is our confession merely an exercise in feeling bad about ourselves, in self-flagellation? As Jay said to us in his sermon last night, “Our sense of immense guilt over our sins, collective and individual, could paralyze us. How do we move forward with teshuvah when the task is so great?”

According to Jewish law, the first step in teshuvah is simply recognizing that a wrong has been committed and confessing openly to it. This in and of itself is no small thing. I daresay with all of the media attention to the Syrian refugee crisis, there is precious little, if any, discussion of the ways our nation might be complicit in creating it. And here at home, we are far from a true reckoning over the ways our white supremacist legacy has dislocated Native Americans and people of color in our own country. And needless to say, the Jewish community continually rationalizes away the truth of Israel’s ongoing injustice toward the Palestinian people.

So yes, before we can truly atone, we must first identify the true nature of our wrongdoings and own them – as a community – openly and together. The next step is to make amends – to engage in a process of reparations to effect real transformation and change. But again, the very prospect of this kind of communal transformation feels too overwhelming , too messianic to even contemplate. How do we even begin to collectively repair wrongs of such a magnitude?

I believe the answer, as ever, is very basic. We begin by joining together, by building coalitions, by creating movements. We know that this kind of organizing has the power to effect very real socio-political change in our world. We have seen it happen in countries such as South Africa and Ireland and we’ve seen it here at home – where Chicago became the first city in the country to offer monetary reparations to citizens who were tortured by the police. In this, as in the aforementioned examples, the only way reparations and restorative justice was achieved was by creating grassroots coalitions that leveraged people power to shift political power.

And that is why we’ve prominently identified “solidarity” as one of our congregation’s six core values:

Through our activism and organizing efforts, we pursue partnerships with local and national organizations and coalitions that combat institutional racism and pursue justice and equity for all. We promote a Judaism rooted in anti-racist values and understand that anti-Semitism is not separate from the systems that perpetuate prejudice and discrimination. As members of a Jewish community, we stand together with all peoples throughout the world who are targeted as “other.”

How do we effect collective atonement? By realizing that we are not in this alone. By finding common cause with others and marching forward. It is not simple or easy work. It can be discouraging and depleting. It does not always bear fruit right away and it often feels as if we experience more defeats than successes along the way. But like so many, I believe we have no choice but to continue the struggle. And I am eager and excited to begin to create new relationships, to participate as a Jewish voice in growing coalitions, with the myriad of those who share our values. I can’t help but believe these connections will ultimately reveal our true strength.

I’d like to end now with a prayer – I offer it on behalf of refugees and migrants, on behalf of who have been forced to wander in search of a home:

Ruach Kol Chai – Spirit of All that Lives:

Help us. Help us to uphold the values that are so central to who we are: human beings created in the image of God. Help us to find compassion in our hearts and justice in our deeds for all who seek freedom and a better life. May we find the strength to protect and plead the cause of the dislocated and uprooted, the migrant and the refugee.

Guide us. Guide us toward one law. One justice. One human standard of behavior toward all. Move us away from the equivocation that honors the divine image in some but not in others. Let us forever affirm that the justice we purport to hold dear is nothing but a sham if it does not uphold basic human dignity for all who dwell in our midst.

Forgive us. Forgive us for the inhumane manner that in which we too often treat the other. We know, or should, that when it comes to crimes against humanity, some of us may be guilty, but all of us are responsible. Grant us atonement for the misdeeds of exclusion we invariably commit against the most vulnerable members of society: the uprooted and unwanted, the unhoused, the uninsured, the undocumented.

Strengthen us. Strengthen us to find the wherewithal to shine your light into the dark places of our world. Give us ability to uncover those who are hidden from view, locked away, forgotten. Let us never forget that nothing is hidden and no one lost from before you. Embolden us in the knowledge that no one human soul is disposable or replaceable; that we can never, try as we might, uproot another from before your sight.

Remind us. Remind us of our duty to create a just society right here, right now, in our day. Give us the vision of purpose to guard against the complacency of the comfortable – and the resolve in knowing that we cannot put off the cause of justice and freedom for another day. Remind us that the time is now. Now is the moment to create your kingdom here on earth.

Ken Yehi Ratzon. May it be your will. And may it be ours.

And let us say,

Amen.

On Yom Kippur, journalist Max Blumenthal delivered this powerful presentation during the afternoon program at

On Yom Kippur, journalist Max Blumenthal delivered this powerful presentation during the afternoon program at