The Jewish interwebs have been abuzz regarding Yair Rosenberg’s December 17 Tablet article in which he criticized the New York Times Book Review for its interview with Alice Walker. In last Sunday’s “By the Book” column, the Times asked Walker what books she had on her nightstand; among those she cited was a book by British antisemitic conspiracy theorist David Icke entitled, “And the Truth Shall Set You Free.” Walker commented, “In (his) books there is the whole of existence, on this planet and several others, to think about. A curious person’s dream come true.”

In his article, Rosenberg listed a litany of odious excerpts from Icke’s book, including his praise of “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” his claims that the B’nai B’rith was behind the slave trade and his belief that the Rothschilds bankrolled Adolf Hitler. He also offered a long list of the numerous times Walker has endorsed Ickes’ ideas, including her posting of his video interview (now blocked by YouTube) with Infowars’ Alex Jones, of which she wrote:

I like these two because they’re real, and sometimes Alex Jones is a bit crazy; many Aquarians are. Icke only appears crazy to people who don’t appreciate the stubbornness required when one is called to a duty it is impossible to evade.

Rosenberg also posted in full, a deeply disturbing poem written by Walker in 2017 entitled “It is Our (Frightful) Duty to Study the Talmud.” This excerpt should give you a good idea about the tone and substance of Walker’s piece:

For a more in depth study

I recommend starting with YouTube. Simply follow the trail of “The

Talmud” as its poison belatedly winds its way

Into our collective consciousness.

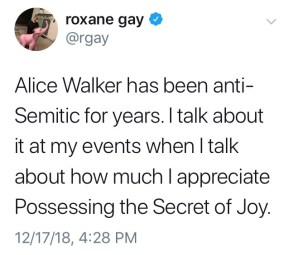

I will sadly confess that I was unaware of Alice Walker’s history of antisemitic attitudes, even though this was apparently common knowledge among many on the left. During the Twitter eruption that followed Rosenberg’s piece for instance, Roxane Gay commented:

Those of us who were hearing of Walker’s antisemitic proclivities for the first time were particularly saddened to learn that this eloquent champion of anti-racism had been expressing such poisonous ideas toward Jews and Judaism. Journalist/filmmaker Rebecca Pierce spoke for many of us when she tweeted this response:

In his article, Rosenberg made mention of Walker’s anti-Israel politics, challenging “the progressive left” to call out antisemitism that is “presented in the righteous guise of ‘anti-Zionism.’” Although I don’t share Rosenberg’s conservative Israel politics, I accept his challenge. And yes, it’s painfully true that Walker’s Talmud poem egregiously cites Jewish religious tradition as the root cause of Israel’s oppression of Palestinians (as well as American police brutality, mass incarceration and “war in general”):

For the study of Israel, of Gaza, of Palestine,

Of the bombed out cities of the Middle East,

Of the creeping Palestination

Of our police, streets, and prisons

In America,

Of war in general,

It is our duty, I believe, to study The Talmud.

It is within this book that,

I believe, we will find answers

To some of the questions

That most perplex us.

Walker’s claim that the Talmud is “evil” and “poisonous” – a common antisemitic trope – is worth unpacking here. First of all, what is referred to as “The Talmud” is actually a vast corpus of Jewish civil and ritual law mixed with freewheeling legend and Biblical commentary composed between 200 and 500 CE. Though it is one of Jewish tradition’s foundational texts, Talmudic literature is not, to put it mildly, immediately accessible to the untrained reader. It’s typically studied by traditional Jews in the rarified world of schools known as yeshivot, where students’ primary focus is on the unique pedagogy of Talmudic argumentation.

Like all forms of religious literature, Talmudic tradition expresses a wide spectrum of ideas and attitudes. The contemporary reader would likely find its content to be alternately inscrutable, inspiring, challenging, archaic – and yes, at times even repugnant. It contains passages for example, that are profoundly misogynistic. And as Walker pointed out in her poem, it also contains occasional material that is decidedly anti-Gentile, including a notorious passage that depicts Jesus condemned to suffer in hell in a vat of burning excrement. (Yep, it’s true.) There are also texts that unabashedly claim Jewish lives must take precedence over non-Jewish lives – an idea that was also advocated centuries later by Moses Maimonides.

These texts are undeniably, inexcusably offensive and they must be called out, full stop. At the same time however, it is exceedingly disingenuous to judge a religion on the basis of its most problematic pronouncements. This attitude simplistically accepts these texts at face value, devoid of any context or historical background. It also ignores the fact that almost all faith traditions address the offensive, archaic or inconsistent elements in their sacred literature through the use of hermeneutics – that is, principles and methods that help readers understand their meaning in ever-changing societal contexts.

How for instance, might a contemporary religious feminist read and understand a blatantly misogynist Talmudic text? In an article entitled “When Sages are Wrong: Misogyny in Talmud,” Dr, Ruhama Weiss, of Hebrew Union College offers one hermeneutical approach:

(These Talmudic traditions) caused me a powerful disturbance. They forced me to think and react; to think about mechanisms of power and control and about the ability to be free from them. To make an effort to find and highlight additional voices, earlier voices, buried and hidden in misogynist rabbinic discussions.

Most importantly, these difficult sources teach me a lesson in modesty; from them I learn that unequally talented and wise people with good intentions can bequeath to subsequent generations difficult and bad traditions. I see the moral blind spots of my ancestors, and I am obligated to examine my own moral blind spots. Bad and disturbing sources make me think.

Indeed, this same hermeneutic method can be applied to Talmud’s xenophobic, anti-Gentile content as well. That is to say, these texts can challenge us to see “the moral blind spots of our ancestors and thus to examine our own moral blind spots.” They can help us confront “mechanisms of power and control” and contemplate the ways we might be able to “free ourselves of them.” These bad and disturbing sources can “make us think.”

Of course there are those who will read the texts of their faith through a more literal, fundamentalist hermeneutic. In such cases, it is up to those who cherish their religious tradition and the value of human rights for all to challenge such interpretations, particularly when the lines between church and state power become increasingly blurred.

On the subject of state power, I must add that I find it exceedingly problematic when folks criticize Talmudic tradition for its xenophobic attitudes without acknowledging the fundamentally anti-Jewish attitudes that are embedded deep within Christian religious tradition. It’s also important to note that antisemitic church teachings were historically used to inspire centuries of anti-Jewish persecution throughout Christian Europe, while the Talmud was written and compiled in a context of Jewish political powerlessness.

Today, in this relatively new era of Jewish power, it is certainly important to remain vigilant over the ways Jewish tradition is used to justify the oppression of Palestinians. Indeed, since the establishment of the State of Israel, this subject has been intensely debated throughout Israel and the Jewish Diaspora. As I write these words in fact, I’m recalling a blog post I wrote back in 2009 about then Chief Rabbi of the Israeli Defense Forces Avichai Rontzki, who made a comment, based on Jewish religious texts, that soldiers who “show mercy” toward the enemy in wartime will be “damned”:

How will we, as Jews, respond to the potential growth of Jewish Holy War ideology within the ranks of the Israeli military? How do we feel about Israeli military generals holding forth on the religious laws of warfare? Most Americans would likely agree that in general, mixing religion and war is a profoundly perilous endeavor. Should we really be so surprised that things are now coming to this?

I do not ask these questions out of a desire to be inflammatory. I ask them only because I believe we need to discuss them honestly and openly – and because these kinds of painful questions have for too long been dismissed and marginalized by the “mainstream” Jewish establishment.

In the end, every faith tradition has its good, bad and ugly. And in the end, I would submit that the proper way to confront these toxic texts is for people of faith to own the all of their religious heritage – and to grapple with it seriously, honestly and openly. And while we’re at it, it’s generally a good rule of thumb to avoid using the bad, ugly stuff in any religion’s textual tradition to make sweeping historical or political claims about that religion and/or the folks who adhere to it.

What is not at all helpful is for people such as Alice Walker to cherry-pick and decontextualize quotes from one particular religious tradition and warn that its “poison” is “winding its way into our collective consciousness.”

Like many of my friends who are just now learning about her adherence to antisemitic tropes, I fervently hope she will come to understand, as Rebecca Pierce put it, that the attitudes she endorses “are part of the same white supremacist power structure she so deftly fought through her written work in the past.”

Here are the remarks that Jay Stanton offered at Tzedek Chicago’s Passover seder last night. Jay was formerly Tzedek’s rabbinical intern – and I’m delighted to announce we’ve just hired him to be part of our staff for the coming year:

Here are the remarks that Jay Stanton offered at Tzedek Chicago’s Passover seder last night. Jay was formerly Tzedek’s rabbinical intern – and I’m delighted to announce we’ve just hired him to be part of our staff for the coming year: